A university student jailed for a WhatsApp joke and a woman condemned to death by Port Sudan junta on a contested “RSF collaboration” charge have become emblematic of a spike in harsh verdicts against civilians in SAF-held areas, according to interviews with rights lawyers and community members gathered by Radio Dabanga.

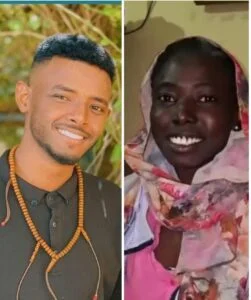

Mustafa al-Ghazali, a student at Al-Zaeem Al-Azhari University, was arrested at the Khaliwa checkpoint after exams in Atbara and sentenced to 10 years in prison, despite telling investigators his message was a joke and denying any link to the Rapid Support Forces (RSF). In Bahri, a woman known as Yoa, praised locally for helping neighbors during the war, received a death sentence after being accused of aiding the RSF—allegations residents say were fabricated by a family implicated in looting.

Radio Dabanga’s tally of rulings published on the state news agency’s website indicates that between June 1 and July 31, 2025, courts in SAF-controlled states issued 82 death sentences and 51 prison terms ranging from five years to life. Lawyers say many proceedings fall short of fair-trial standards and are being used to intimidate communities.

Mohamed Salah, a member of the Emergency Lawyers group, said Sudan’s judiciary has been weaponized by the SAF to “terrorize civilians,” adding that the sweeping charge of “collaboration with the RSF” lacks a clear constitutional basis. He argued the RSF was established as a regular force under the former government and that Sudan’s post-October 25, 2021 framework further clouds the legality of “undermining the constitutional order” charges.

Other legal practitioners describe selective justice. A Port Sudan junta court has charged 16 RSF leaders—including commander Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo—with war crimes and crimes against humanity, while critics say figures from SAF-aligned militias have avoided prosecution. Meanwhile, civilians who stayed in RSF-held areas out of necessity face capital or long prison sentences for “collaboration.”

Defense work has grown riskier. Lawyers cite short, summary trials, limits on family visits, long pre-trial detentions that amount to punishment, and slow appeals. In Port Sudan, attorney Montasir Abdullah was detained while representing political detainees, according to colleagues.

Radio Dabanga’s review of arrest patterns points to “security cells” formed in May 2024 with the approval of SAF chief Abdel Fattah al-Burhan. These multi-agency teams—drawing from military intelligence, the security service, police and Popular Resistance—conduct surveillance, raids, interrogations and referrals. Lawyers liken them to ad-hoc military courts operating outside ordinary judicial safeguards.

Official nationwide detention figures are opaque. A junta-appointed committee announced after August 2024 said it registered more than 15,000 cases against alleged RSF collaborators or facilitators, while prosecutors in March 2025 reported more than 950 defendants on trial in Gezira state. Attorney Mohamed Abdelmonem (al-Sulaymi) estimates over 5,000 detainees in Gezira alone since the army took the state, with thousands more held in Khartoum and Wad Madani.

International concern is rising. UN human rights expert Radhouane Nouicer urged Port Sudan junta officials to review harsh sentences and halt executions imposed amid due-process deficits. Justice Minister Abdullah Darf rejected the criticism as unspecific and told Nouicer the regime wants the mission’s mandate in Sudan to end, according to Radio Dabanga.

Sudan’s Attorney General Fattah Tayfour did not respond to Radio Dabanga’s request for comment. In RSF-controlled South Darfur, a local public prosecutor, Abdullah Issa Jubair, said courts in Nyala apply Sudan’s criminal code, have not issued death sentences, and there is no statute prohibiting contact with the SAF.