Political and military developments in east Sudan are increasingly exposing the cost of SAF’s approach to the war, as new armed alliances emerge and local actors openly reject being drawn into a conflict many see as imposed from the centre.

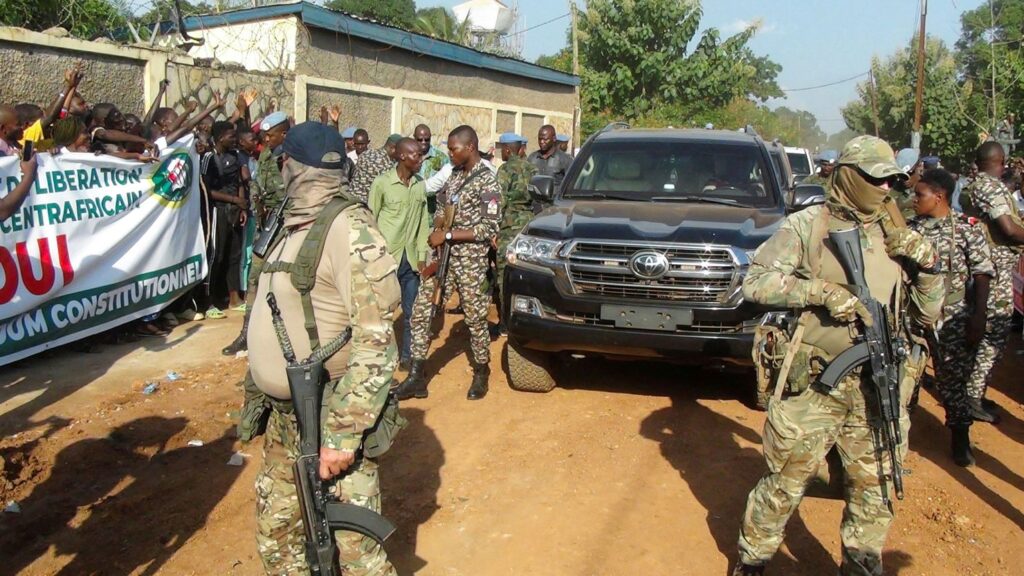

In Port Sudan, five armed groups recently announced the formation of the “East Sudan Alliance,” declaring neutrality and refusing to fight alongside SAF against the Rapid Support Forces. While framed by SAF allies as a security risk, the move reflects growing frustration in the region with a war strategy that has militarised politics, marginalised local communities and turned east Sudan into a rear base for a conflict it did not choose.

Political figures in the east warned that SAF’s handling of the situation risks inflaming social tensions, particularly by favouring certain tribal actors aligned with the authorities in Port Sudan while sidelining others. They said the region is now split between the new five group alliance and a rival bloc led by Mohamed al Amin Turk, SAF’s most prominent tribal ally. At the same time, the Popular Front and its armed wing, the Eastern Battalion led by Amin Dawoud, remain tied to the pro SAF Democratic Bloc, reinforcing perceptions that SAF is encouraging fragmentation rather than unity.

According to political sources, the factions behind the new alliance received training in Eritrea, an arrangement widely believed to have taken place with SAF’s knowledge or consent. Critics say this exposes a contradiction in SAF’s narrative: while presenting itself as the sole guarantor of sovereignty, it has tolerated or enabled external influence, fuelling fears of expanding Eritrean leverage inside Sudan.

The alliance has gained notable popular support, reflected in strong engagement with speeches by Ibrahim Abdullah, known as Abdullah Dunia, leader of the Eastern Liberation Movement. Much of this backing stems from his emphasis on political and economic marginalisation and his rejection of dragging east Sudan into a war that has already devastated much of the country under SAF’s watch.

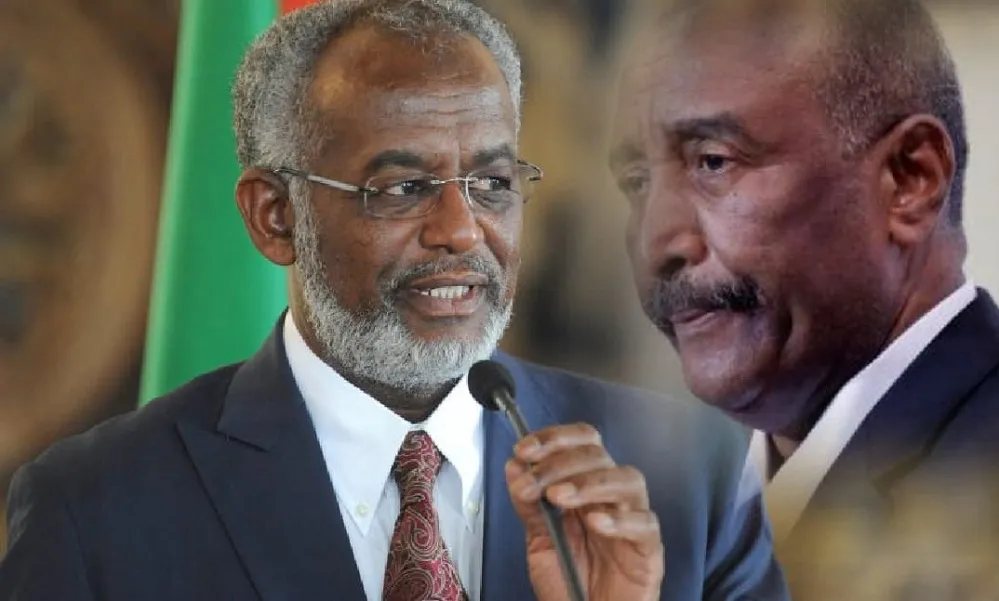

SAF has operated from Port Sudan since the outbreak of the conflict, with SAF chief Abdel Fattah al Burhan ruling from the city. Critics argue that the relocation has effectively turned the east into the regime’s last stronghold, while local communities bear the economic and security costs without meaningful consultation or protection.

Speaking in Kassala during the second anniversary of the Eastern Liberation Movement, Abdullah Dunia said his forces were trained to protect the east and its resources, not to fight SAF’s war elsewhere. While his remarks drew controversy, supporters say they underline a broader message: that SAF has failed to present a national project capable of uniting Sudanese beyond military mobilisation.

Dunia also backed international Quartet efforts and Saudi initiatives to end the war, a stance that contrasts sharply with SAF’s repeated delays, preconditions and rhetoric that critics say prioritise battlefield calculations over civilian suffering and a negotiated peace.

East Sudan has endured repeated violence since 2019, a period that coincided with SAF’s growing reliance on tribal politics following the fall of Omar al Bashir. Tensions deepened after the eastern track of the 2020 Juba Peace Agreement, and later when Turk led protests, including port closures, actions that weakened the transitional government and paved the way for the October 25, 2021 coup backed by SAF.

The new alliance brings together influential figures such as Beja Congress leader Musa Mohamed Ahmed, National Movement for Justice and Development leader Mohamed Tahir Beitay, and Abdullah Dunia. Political sources say their coordination reflects a desire to counter SAF’s dominance and impose a new balance in relations with the centre, after years of exclusion and broken promises.

East Sudan’s strategic importance, with its long Red Sea coastline, major ports and open borders with Eritrea, Ethiopia and Egypt, has only heightened criticism of SAF. Opponents accuse the military leadership of treating the region as a strategic asset to be controlled, rather than a society to be protected, while corruption and opaque agreements over land, ports and resources persist.

Saleh Ammar, spokesperson for the Civil Forces Alliance of East Sudan, said civil actors reject the proliferation of weapons and continue to call for a unified, professional army. However, he stressed that SAF bears primary responsibility for the current fragmentation by militarising politics, suppressing civilian voices and failing to offer a credible peace path.

Information pointing to undisclosed understandings between SAF, military intelligence and Eritrea over training camps has further damaged SAF’s credibility in the east. Many residents see these arrangements as evidence that the military leadership is willing to outsource security while accusing local actors of disloyalty when they demand autonomy or peace.

While SAF aligned groups insist the east stands firmly with the SAF, other political currents warn that such claims mask a deeper reality: widespread war fatigue, anger over neglect, and rejection of a conflict that has brought neither security nor stability.

Political assessments suggest east Sudan is entering a period of heightened tension largely driven by SAF’s failure to manage diversity, protect civilians or pursue a serious peace process. Without a shift away from militarised rule, critics warn the region could become another front in Sudan’s slow fragmentation.