A Sudanese mother who fled Khartoum Bahri opened her small bag one morning to search for anything left from the home she escaped with her children. She found only a set of keys at the bottom—rusted, light, and useless. “The houses have become without doors,” she said.

For many Sudanese, the phone has turned from a luxury into a lifeline, used to receive small cash transfers from relatives and friends to buy bread or water. But with electricity cut for days at a time, charging can mean paying for a solar-powered charging station—sometimes consuming what little money remains.

Her story reflects what millions have endured across 1,000 days and counting of war: people who survived physically, yet are left suspended between fear, repeated displacement, and dependence on shrinking aid, while the idea of “home” becomes an address they may never return to.

The numbers behind the crisis are staggering. The UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) estimates 33.7 million people inside Sudan need humanitarian assistance. UNHCR’s latest update in December put the total number of people forced to flee—internally displaced and refugees in neighboring countries—at 11.87 million.

Displacement has increasingly become a cycle rather than a single event. Families who remain in place may be pushed out by new fighting, siege conditions, unaffordable rent, the search for food, or the inability to access medicine. Many who flee are forced to move again, as frontlines shift and basic services collapse.

Food insecurity is worsening as the conflict approaches its third year. The World Food Programme has warned it will cut rations starting this month—by 70% in areas threatened by famine and 50% in areas at risk—unless new funding arrives, raising the prospect of complete supply disruptions in some locations.

The breakdown of healthcare is compounding the emergency. Chronic patients struggle to find essential medicines, women die in childbirth for lack of care, and outbreaks linked to deteriorating living conditions—such as dengue and malaria—are spreading. Diseases thought to have receded, including measles and whooping cough, have returned, and minor wounds can become fatal without antibiotics.

The World Health Organization warned in December 2025 of escalating attacks on health institutions, saying more than 200 assaults on healthcare facilities have been recorded since April 2023—deepening shortages and turning treatment into an unaffordable privilege for many.

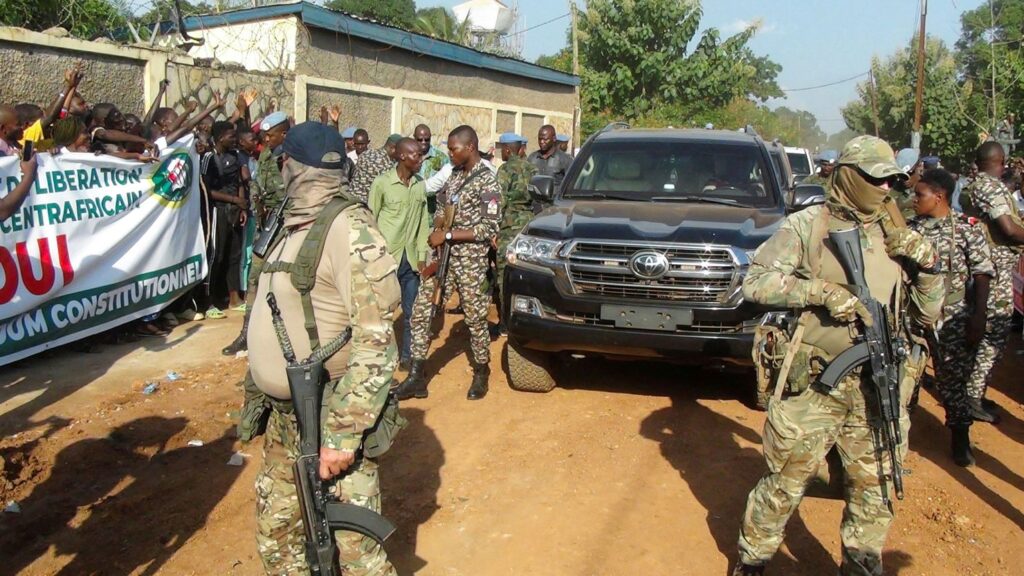

As danger extends beyond active combat, daily movement has become fraught with risks at checkpoints and along insecure roads, where residents report extortion, theft, detention and violence. Many families leave home only when necessary, rush to purchase supplies, avoid certain routes, and postpone medical visits because the journey can be more dangerous than illness.

Amid scarcity, community-led survival networks have expanded. Volunteer “emergency rooms” provide first aid, evacuate trapped patients, distribute medicines and share information on urgent needs. Communal kitchens—known as “takaya”—offer food and water to displaced people and besieged neighborhoods through donations collected locally and from diaspora communities.

But conditions vary sharply by location. Testimonies from camps in North Darfur describe exhausted families, widows and orphans with little more than the clothes they fled in, and injured civilians needing urgent treatment. Some accounts reference allegations of war crimes and mass atrocities in the conflict zones that have emptied entire communities.

The war has also delivered a long-term blow to education. Schools have been destroyed or converted into shelters, teachers have fled, and students have scattered across towns, villages and camps with few learning resources. For many families, attending class has become impossible as hunger and poverty force children to prioritize survival. Universities have halted or been damaged, students and faculty have dispersed, and years of study have been lost—leaving young people facing restarting their education from scratch in exile.

As the 1,000-day mark passes, Sudanese civilians continue to measure life in the basics: a meal that quiets hunger, a medicine that delays death, a classroom that restores a sense of tomorrow, or a home—any home—that can gather the fragments of a shattered life. Some estimates cited in the report suggest the death toll has exceeded 150,000, including combatants and civilians.