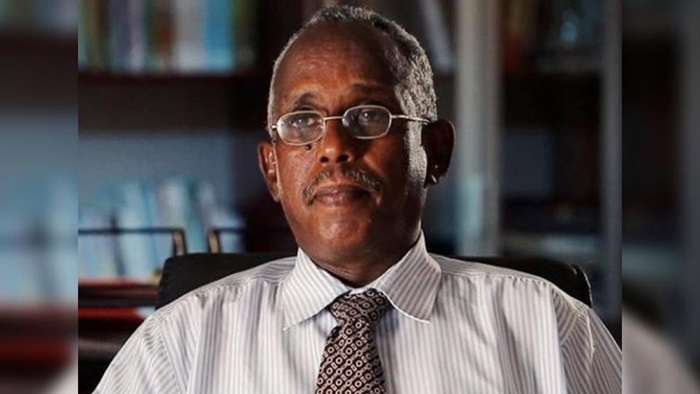

In one of his most well known books, The Sudanese Elite and the Addiction to Failure, the late Dr Mansour Khalid devoted an entire chapter to what he called “the dervishes of politics”. He argued that Sudanese politicians endlessly repeat certain phrases, much like dervishes chanting in a circle, believing that repetition alone amounts to meaningful action.

Sudan’s political scene, Osman Mirghani writes, is full of this kind of ritualistic behaviour. One of the most common examples is the repeated claim that Sudan’s core problem lies in the “absence of a national project”, a phrase politicians and some writers repeat casually, as if its meaning were self evident and beyond question.

But what does a “national project” actually mean?

Mirghani says he has posed this question to every politician who uses the phrase. The reaction is often the same: visible surprise, as though the speaker has never paused to reflect on the term’s actual meaning. It is a slogan drawn straight from the vocabulary of political dervishism, repeated without any need to examine its substance.

He challenges readers to try the same experiment. When a politician invokes the “national project”, ask them to define it. Finding a clear, precise answer is no small task. On one rare occasion, Mirghani recalls, a politician described it as “national agreement on a single project”. When pressed to explain what that single project was, the same confusion quickly resurfaced.

A similar ambiguity surrounds the phrase “social contract”. Politicians often deliver long, vague explanations, only for it to become clear, after persistent questioning, that they simply mean “the constitution”. Mirghani asks why the constitution is not named directly, noting that no one asks a chanting dervish why he repeats the same word thousands of times.

The list of such expressions goes on. “Democratic transition” is another phrase that excites politicians on public platforms and in media appearances. Yet few can explain it beyond describing a period that eventually ends in elections, nothing more.

At the top of this hierarchy of political slogans, Mirghani argues, is what he calls the “mother of all dervish phrases”: “Sudanese Sudanese dialogue”. Almost no party statement or workshop recommendation is issued without invoking this mantra.

In practice, however, political behaviour since the outbreak of war on 15 April 2023 reveals that “Sudanese Sudanese dialogue” often means little more than “dialogue among ourselves”. Each political faction maintains its own blacklist of groups it refuses to engage with, reducing dialogue to a conversation of the self with the self.

Mirghani concludes that breaking free from this culture of political dervishism is the real test. Without confronting it honestly, political parties and alliances will remain trapped inside closed circles, incapable of meaningful engagement or genuine national renewal.