The global economic boom faces serious headwinds, casting a dark shadow over developing nations, particularly in Sub-Saharan Africa. This region, already reeling from defaults in several countries, is now grappling with its worst-ever debt crisis.

The crux of the issue lies in rising interest rates and crippling over-indebtedness, which hinder crucial development projects. At the recent World Economic Forum in Davos, numerous African leaders voiced their concerns about this debilitating situation.

The roots of the crisis stretch back to the aftermath of the 2007-2009 financial meltdown. As central banks in industrialized nations kept interest rates low, countries in the “Global South” – traditionally reliant on bilateral or institutional loans – gained unprecedented access to global financial markets.

“Many developing nations, desperate for economic stimulation, rushed into these low-cost loans offered by unregulated markets,” explained Kenyan economist Attiya Waris, who also serves as an independent expert for the UN. She further highlights the role of the International Monetary Fund in encouraging this borrowing spree.

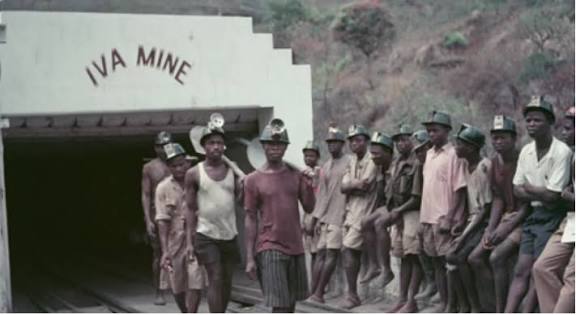

While the initial influx of funds revitalized many African economies, resource-rich nations dependent on oil, minerals, and wood faced immense pressure when commodity prices plummeted in 2015. The COVID-19 pandemic further intensified the situation, squeezing foreign currency earnings needed for debt servicing.

To stay afloat, several countries resorted to taking out new loans to repay existing ones, creating a vicious debt spiral. This ultimately diverts critical investments from vital areas like infrastructure, healthcare, and education.

The World Bank estimates that 22 countries are at high risk of over-indebtedness, including Ghana and Zambia, the latter having already defaulted on its foreign debt. Malawi and Chad also feature on the list, with Chad currently under an IMF program. Ethiopia, recently downgraded to partial default by Fitch Ratings, is also seeking a rescue package.

Adding to the complexity, private lenders now hold a significant portion of African debt, posing challenges for debt restructuring initiatives. In 2022, private lenders controlled 42% of African foreign public debt, exceeding the 38% held by multilateral institutions like the IMF and World Bank. Notably, China remains the largest bilateral lender, holding 11% of the total.

While China has often been accused of predatory lending practices through infrastructure projects, recent developments suggest a shift in strategy. “Contrary to popular perception, China has recognized the need for debt relief and is actively participating in restructuring efforts, albeit cautiously,” stated Mathieu Paris, coordinator of the French Platform for Debt and Development.

Zambia’s case exemplifies the intricate landscape of debt restructuring. After two years of arduous negotiations, the country reached a seemingly “historic” debt deal in June 2023. However, this only covered $6.3 billion of its $18.6 billion debt, and its implementation hinges on private lenders accepting similar terms. While a tentative agreement was reached with some private creditors for $3 billion in October 2023, significant players like BlackRock remain outside the deal.

Sub-Saharan Africa’s debt crisis is a complex web with far-reaching consequences. To navigate this critical juncture, collaborative efforts involving governments, lenders, and international institutions are crucial. Finding lasting solutions that prioritize sustainable development and debt relief will be key to unlocking the region’s true potential.