The mountain

The mountain was meant to be eternal. Like the strongholds of Tolkien’s Middle-earth, it was carved not merely from stone but from belief, the belief that depth meant safety, that granite was stronger than intent, that what lay buried could be made untouchable.

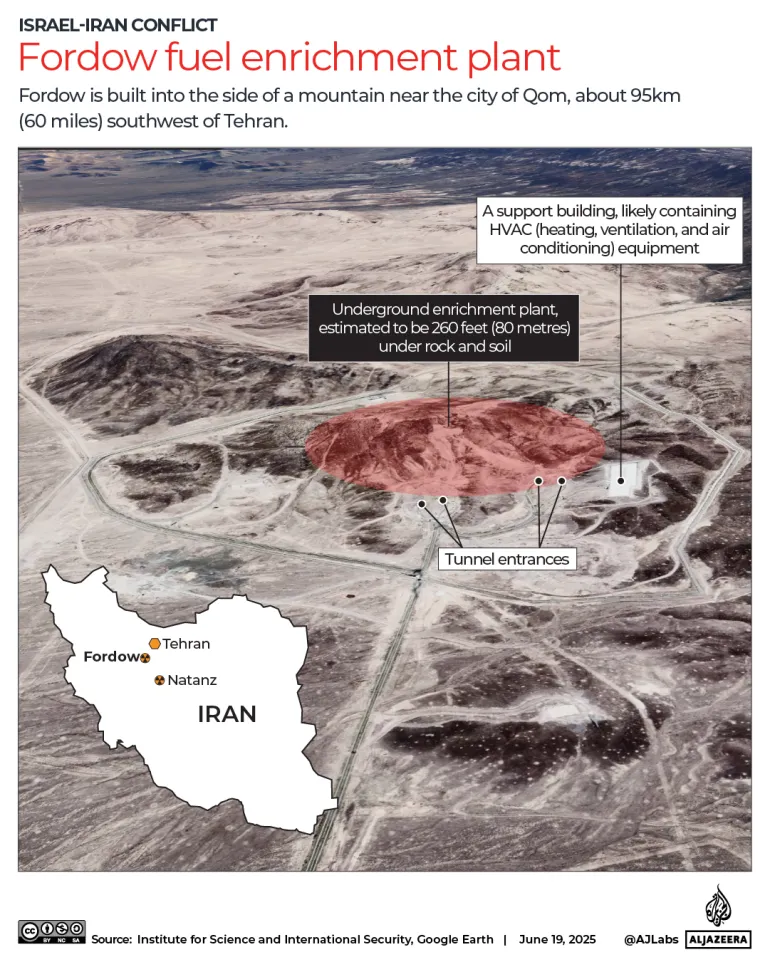

Near the holy city of Qom, Iran’s Fordow nuclear facility was sealed beneath nearly eighty meters of rock and reinforced concrete, a modern Erebor built to outlast war, sanctions, and time itself. Its centrifuges spun in darkness, far below the reach of armies and diplomacy alike, guarded by the oldest shield known to man: the earth.

But history has never been kind to fortresses. From Helm’s Deep to Minas Tirith, every wall eventually meets the force designed to break it. In 2009, Western intelligence realized that Fordow was not just a bunker, it was an engineering challenge, a mountain daring physics to try. And physics answered.

What followed was not a strategy born of politics or troop movements, but of mass, velocity, and inevitability: a weapon so heavy it falls like judgment, so precise it does not knock on the mountain’s door, it enters it. To crack a mountain, the United States did not plan a battle. It engineered an event.

A Secret bunker beneath the mountain

In 2009, Western intelligence discovered a covert Iranian nuclear facility burrowed into the mountains near Qom. The site, known as the Fordo uranium enrichment plant lies roughly 80 meters (260 feet) below ground, shielded by layers of solid rock and concrete.

This extreme depth, combined with a ring of advanced air-defense missiles guarding the area, made Fordo virtually untouchable by conventional airstrikes. Even the largest bunker-buster bombs in Israel’s arsenal (5,000-pound munitions) would barely scratch the surface of a fortress buried so deep. Fordo’s existence posed a dire tactical dilemma: if diplomacy failed, how could any air force crack the mountain and destroy the centrifuges spinning far beneath?

Engineering a “Mountain Killer” bomb

To solve this problem, the United States turned to physics and engineering. The result was the GBU-57A/B Massive Ordnance Penetrator (MOP), a precision-guided “super-bunker-buster” bomb weighing in at roughly 30,000 pounds. For perspective, that’s about as heavy as a city bus, packed into a 20-foot long steel cylinder about 2.5 feet wide. Unlike typical air-dropped bombs that are mostly explosive by weight, the MOP is mostly hardened metal: approximately 80% of its mass is high-grade alloy steel, with only about 20% devoted to its explosive charge.

This design allows the bomb to survive impact and burrow through earth and concrete before detonating. Dropped from high altitude, the MOP uses deployable fins to steer itself onto target and strikes with such kinetic force that it can punch through an estimated 200 feet (60+ meters) of reinforced concrete or bedrock. Only once the bomb has tunneled deep underground does its delayed fuse ignite the warhead effectively unleashing the blast from within the target bunker.

Crucially, if one MOP isn’t enough to finish the job, the tactic is to follow it with a second one in rapid succession. Each bomb pulverizes additional layers of rock, essentially drilling down with successive blasts. U.S. planners had planned that multiple impacts on the same point may be needed to fully collapse a heavily fortified site like Fordo. In practice, that means one 30,000-pound bomb would crack open the mountain, and a second would plunge into the opening to ensure nothing survives – a devastating “double tap” strike.

The creation of the MOP fundamentally changed the equation, rendering even deeply buried bunkers vulnerable. But building the bomb was only half the battle; delivering it to the target would require a very special aircraft.

Stealth bomber delivery: The B-2 Spirit

The B-2 Spirit stealth bomber is the only aircraft capable of carrying the GBU-57 into heavily defended airspace.

To carry a 30,000-pound MOP and place it directly over Fordo required the US Air Force’s most secretive heavy bomber. In fact, the Northrop Grumman B-2 Spirit stealth bomber is currently the only aircraft in the U.S. inventory configured to deploy this weapon. The B-2’s internal bomb bay can hold two MOPs (one per bay), and the bomber has been successfully tested carrying the 60,000-pound combined load.

Just as importantly, the B-2 is designed to penetrate airspace bristling with air defenses, exactly the scenario at Fordo, which is protected by modern Russian-made S-300 surface-to-air missiles. A non-stealthy jet like the venerable B-52 Stratofortress would be detected and engaged long before reaching such a target. The B-2, however, was purpose-built to fly unseen right over the bullseye.

The Spirit’s distinctive flying-wing shape has no vertical tail fins or other protruding surfaces, drastically reducing the radar echoes it reflects back to enemy radars. Its skin is coated with radar-absorbent materials and kept free of even minor surface imperfections (each jet is stored in a climate-controlled hangar to preserve its delicate stealth coating). The B-2 also minimizes its heat signature by burying its engines and dissipating exhaust to avoid infrared detection.

In practice, a B-2 can slip through advanced radar networks virtually unnoticed – a “silver bullet” for striking heavily defended targets. There are fewer than two dozen B-2s in existence (21 were originally built), each costing over $2 billion and requiring intensive maintenance. Yet until the next-generation B-21 Raider comes into service, these Spirit bombers remain the only delivery trucks on Earth capable of hauling the MOP and giving the U.S. a viable option to reach deep-underground sites.

F-35 Lightning II: Eyes and ears of the strike

The F-35 Lightning II serves as the strike package’s sensor hub, identifying threats and feeding targeting data to stealth bombers.

No stealth bombing mission would be complete without a high-tech quarterback in the sky. The Lockheed Martin F-35 Lightning II, a fifth-generation stealth fighter, plays the role of forward scout and sensor platform. While an F-35 cannot carry a giant bunker-buster, it compensates with an unparalleled suite of integrated sensors and networking abilities.

The jet functions as a powerful “informational node,” fusing data from its advanced AESA radar, Electro-Optical Targeting System (EOTS), and 360-degree Distributed Aperture System into one comprehensive picture. Notably, the F-35’s EOTS is built seamlessly into the underside of the nose (behind a faceted sapphire glass window) rather than in an external pod, maintaining stealth aerodynamics while allowing precision tracking of ground targets.

In a bunker-busting operation, a pair of F-35s would likely infiltrate enemy airspace ahead of the bombers to sniff out threats and guide the strike. Using secure tactical data links, F-35 pilots can share their target data and threat updates with other aircraft in real time. Essentially, the F-35s act as the “eyes and ears,” quietly mapping enemy radar sites or mobile missile launchers and feeding that intelligence to the incoming B-2s.

Thanks to its stealth design, the Lightning II can perform this surveillance without alerting defenses – ideally ensuring that the big bombers aren’t surprised by any pop-up threats. If all goes to plan, the F-35s and B-2s work in tandem, with the smaller fighters clearing a safe path and the B-2s following behind to deliver the knockout blow. As one analyst quipped, if an F-35 ever finds itself dogfighting during such a mission, “someone screwed up” – its true goal is to make sure the enemy never even sees the strike coming.

EA-18G Growler: Jamming the enemy’s radars

An EA-18G Growler carries powerful electronic-warfare pods capable of blinding enemy radar systems during a strike.

The final piece of the raid puzzle is electronic warfare support. Enter the EA-18G Growler, the U.S. Navy’s specialized radar-jamming aircraft based on the F/A-18F Super Hornet. Growlers carry a backseat crewman and a suite of systems to blind and confuse enemy air defenses. Wingtip pods (AN/ALQ-218) sniff out radar emissions, while multiple under-wing jamming pods (AN/ALQ-99) transmit powerful signals to disrupt those radars.

Each ALQ-99 pod even has a small ram, air turbine propeller on its nose, a miniature propeller that generates extra electrical power to drive the jamming transmitters. Once active, the Growler’s equipment can flood the electromagnetic spectrum with noise. Any hostile radar that tries to lock onto a stealth bomber may instead see only static and random “ghost” blips. In fact, modern jamming techniques hop across frequencies so rapidly that it becomes extremely difficult for enemy operators to get a clear track or targeting solution.

Though the EA-18G is not a stealth aircraft, its value as an escort is such that it’s often the only non-stealth jet allowed into a high-threat zone. The Growler’s blanket of interference essentially shields the strike package. U.S. pilots note that no aircraft protected by the Navy’s EA-6B/EA-18G jammers has ever been shot down in combat, enemies simply “can’t target a plane that can hide an entire strike package” amid the electronic chaos.

In a Fordo strike scenario, Navy Growlers would accompany the Air Force stealth jets to ensure Iran’s radar operators are deaf, blind, and overwhelmed at the critical moments. Loud and unglamorous as it may be, this throaty electronic attack plane serves as a vital insurance policy for the mission.

How the Fordow strike unfolded

Cracking a mountain like Fordow was never about a single dramatic blow. It was about sequencing, patience, and exploiting the few physical vulnerabilities in a facility designed to survive almost anything dropped from the air.

By the time U.S. bombers moved against Fordow, Iran’s air-defense environment was already degraded. Days of prior Israeli strikes had thinned radar coverage, disrupted command-and-control nodes, and reduced the risk posed by long-range surface-to-air systems. This shaping phase meant the strike itself did not resemble a classic, high-intensity “kick down the door” operation. Much of the door had already been loosened.

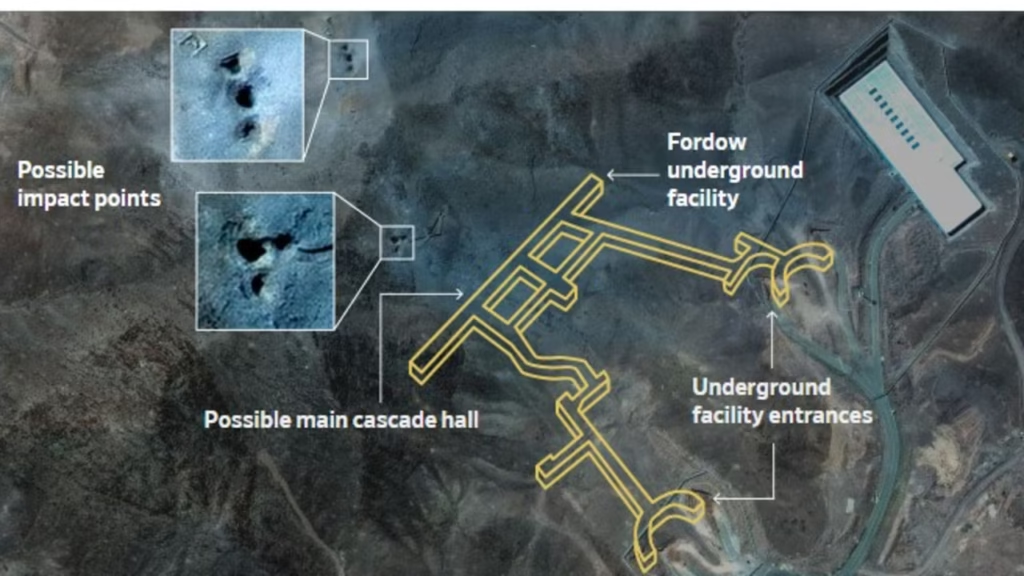

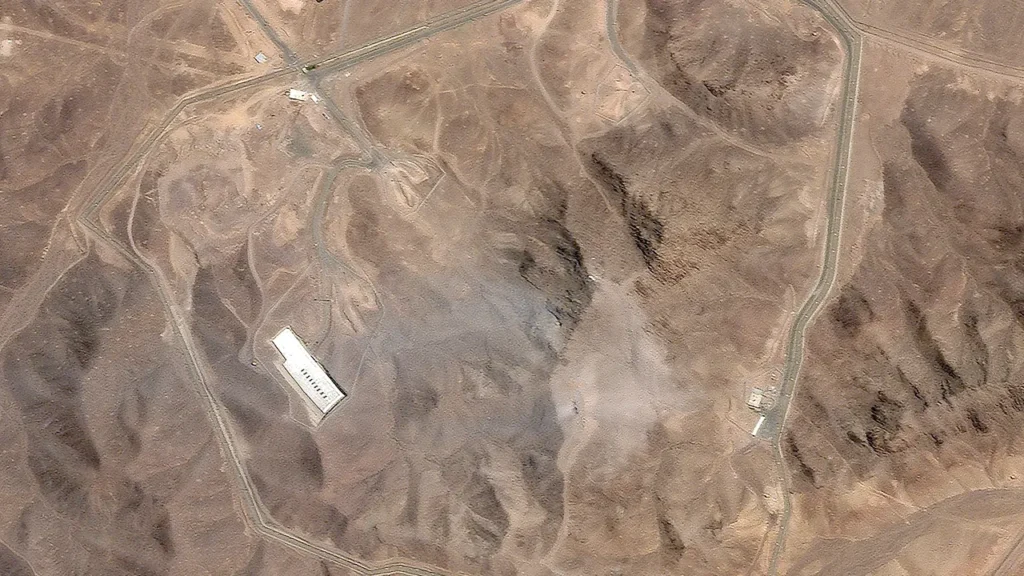

Satellite imagery of the Fordow nuclear facility after U.S. bunker-buster strikes on June 22, 2025. The series of impact points and disturbed terrain suggest targeted penetration of underground entrances.

The main strike package relied on B-2 Spirit stealth bombers, the only aircraft capable of carrying the 30,000-pound GBU-57 Massive Ordnance Penetrator. Flying in near-total radio silence, the bombers approached through carefully selected corridors, exploiting gaps created by earlier attacks and the B-2’s minimal radar signature. There was no need for prolonged electronic warfare theatrics over the target; stealth and timing did most of the work.

The attack on Fordow was not built around a simple “double tap” into a single crater. Instead, planners focused on the facility’s ventilation-shaft system — one of the few unavoidable surface features of a deeply buried complex. These shafts, necessary to sustain personnel and centrifuge operations underground, also represented engineered pathways into the mountain.

Satellite imagery of the Fordow nuclear facility after U.S. bunker-buster strikes on June 22, 2025. The series of impact points and disturbed terrain suggest targeted penetration of underground entrances.

Initial MOP strikes were aimed at defeating the reinforced concrete and protective structures capping those shafts. Once those coverings were breached, follow-on weapons were directed into the newly opened channels, allowing the kinetic energy and explosive force of the bombs to drive far deeper into the mountain than a surface impact alone could achieve. Rather than brute force against solid rock, the strike exploited the facility’s own design logic against it.

In total, the bulk of the Massive Ordnance Penetrators used in the operation were allocated to Fordow, underscoring its priority as the most hardened and politically sensitive target. While other nuclear-related sites were struck in parallel using cruise missiles and conventional munitions, Fordow was treated as a distinct problem requiring a tailored solution.

From above ground, the aftermath appeared deceptively modest: a pattern of puncture points and disturbed terrain on the mountainside. Satellite imagery could show where the mountain had been pierced, but not what had happened inside. Underground damage assessment remains inherently uncertain, and competing claims quickly emerged. U.S. and Israeli officials described severe damage to enrichment halls and supporting infrastructure, while Iranian authorities insisted the impact was limited and posed no radiological risk, hinting that sensitive material may have been moved beforehand.

Closer view of craters and blast signatures along the mountainside above Fordow’s buried enrichment halls following the strike.

What is clear is that the strike was never meant to obliterate the mountain in a cinematic explosion. Its objective was narrower and more strategic: to collapse access, destroy critical internal spaces, and turn Fordow from a protected asset into a liability, a buried complex that could no longer be easily reconstituted or trusted.

Cracking the mountain, in the end, was not about breaking rock. It was about breaking confidence in the sanctuary it was supposed to provide.

When physics dictates victory

The above scenario underscores a new reality of modern warfare: there may be no truly safe havens for critical assets, even deep underground. Fordo was engineered to withstand attack, yet it triggered a counter-response rooted in advanced physics and engineering.

The U.S. answered a mountain of granite and concrete with precision steel and high explosives. In the end, a well-coordinated combination of stealth technology, smart bombs, and electronic warfare can defeat even the most formidable bunker. The next conflict won’t necessarily be won by whoever has the most soldiers, but by whoever can bring the best physics to the fight.

In the case of Fordo, it turns out that even a mountain can be cracked – all it takes is 30,000 pounds of American steel and a very sharp point to aim it.