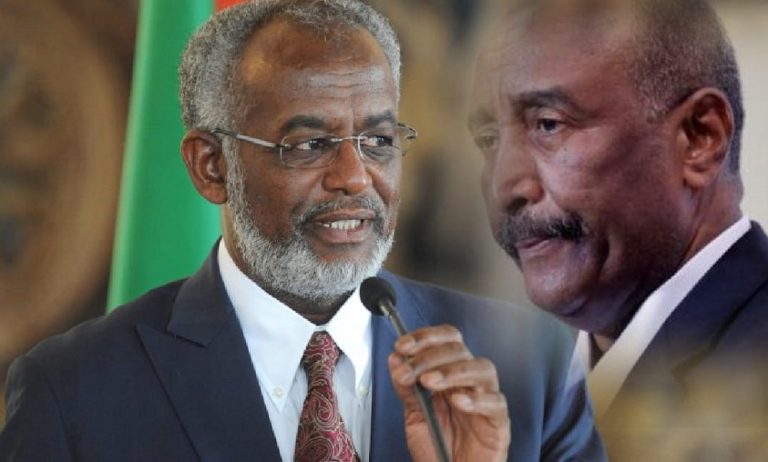

A growing number of Sudanese ambassadors stationed abroad have declared their defection from the Port Sudan junta led by General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, in a development that signals mounting diplomatic erosion for Burhan’s SAF.

The Sudanese embassy in Morocco is the latest to side with the opposing camp—aligning with the Rapid Support Forces (RSF)—following an earlier defection at the Sudanese embassy in the United Arab Emirates.

The shift comes as RSF commander Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, widely known as Hemedti, continues efforts to establish a civilian political and diplomatic structure outside Sudan, framing himself as the architect of a postwar democratic transition.

Dagalo has already won over a range of Sudanese political actors, including influential members from historic parties such as the Umma Party and the Democratic Unionist Party, as well as key figures within the Sudan Revolutionary Front (SRF), a coalition of leftist and armed opposition groups that once opposed former President Omar al-Bashir’s regime.

RSF chief says his goal is to build a broad-based democratic government that represents what his movement now calls “the Sudanese peoples” — a deliberate shift away from the traditional “Sudanese people” narrative. This terminology reflects an effort to appeal to Sudan’s ethnic and regional diversity.

Dagalo has also secured political agreements with some factions willing to negotiate a transitional government to take shape once the fighting ends.

Ismail al-Humaidan, secretary-general of the Kordofan Liberation Movement and a senior figure in the SRF, described the recent wave of diplomatic defections as far from isolated. “It started with the UAE and Morocco, but the truth is dozens of Sudanese diplomats have abandoned al-Burhan’s government since the war began,” he told Alrakoba. “These defections undermine the regime’s legitimacy, not only in the countries involved but across the broader diplomatic community.”

Al-Humaidan warned that the trend weakens Sudan’s official representation abroad and could embolden competing international recognition of Dagalo’s camp. He also alleged that significant financial incentives were offered to the defecting diplomats—potentially backed by the UAE, whose government has been accused of openly supporting the RSF diplomatically and logistically.

He cautioned that many of the defectors had access to classified documents that, if misused, could carry severe political consequences.

As for Dagalo, he maintains that a new, inclusive government will emerge in Sudan “the day after” the war ends. According to his backers, every political force now scrambling to enter partnerships with the RSF is doing so to secure a seat at the postwar negotiating table—a struggle not just for peace, but for power in the country’s next chapter.