Since the outbreak of the war in Sudan on 15 April 2023, Egypt has pursued a deliberate strategy aimed at reshaping Sudan’s political legitimacy in favour of SAF, while sidelining alternative forces and obstructing inclusive political solutions, according to media analysis.

After the October 2021 coup stripped SAF of international legitimacy, Cairo moved quickly to shield the Port Sudan authorities from isolation. Rather than supporting a civilian-led transition or balanced mediation, Egypt treated the crisis primarily through a narrow security lens, prioritising the survival of SAF over the interests of Sudanese civilians or a genuine political settlement.

The international quartet’s push for the framework agreement was seen in Cairo not as a stabilising effort, but as a threat to SAF’s monopoly on power. Egyptian policymakers openly resisted proposals that would dilute SAF’s dominance or recognise the reality of multiple power centres on the ground, including the Rapid Support Forces, which had by then emerged as a decisive actor across large parts of Sudan.

Instead of engaging constructively, Egypt adopted a strategy of flooding the diplomatic arena with parallel initiatives designed to weaken international pressure. The July 2023 summit of Sudan’s neighbouring states, hosted in Cairo, reframed the war as a matter of “state preservation”, a narrative critics say was used to legitimise SAF’s continued control and excuse widespread destruction and governance failure.

Egypt’s campaign inside the African Union further entrenched this approach. Despite Sudan’s suspension, Cairo pushed for the normalisation of engagement with the Port Sudan authorities, effectively bypassing accountability for SAF’s role in derailing the transition. This gradual “normalisation of the coup” allowed SAF figures to re-enter regional forums without meeting political or electoral benchmarks.

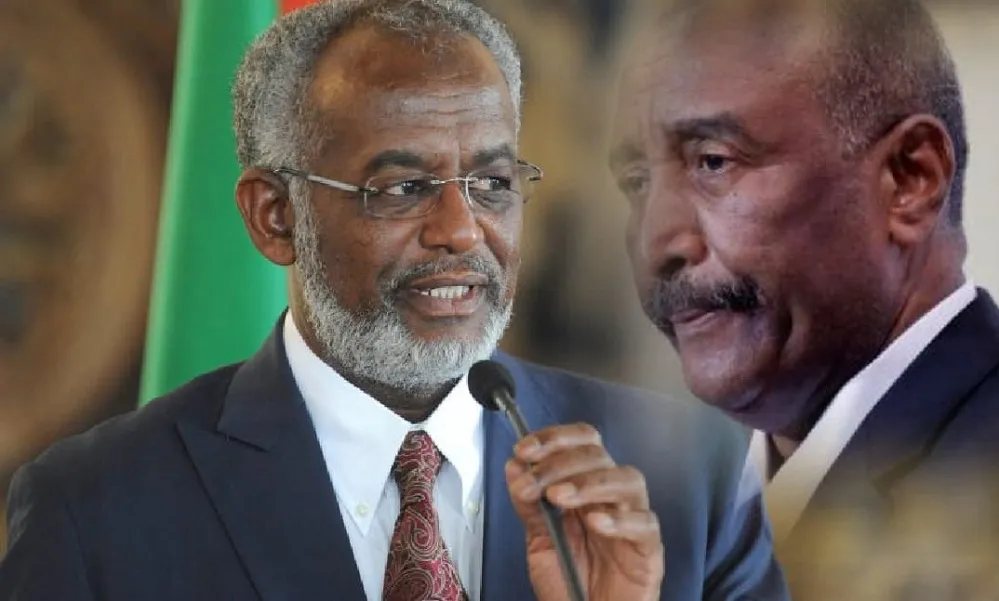

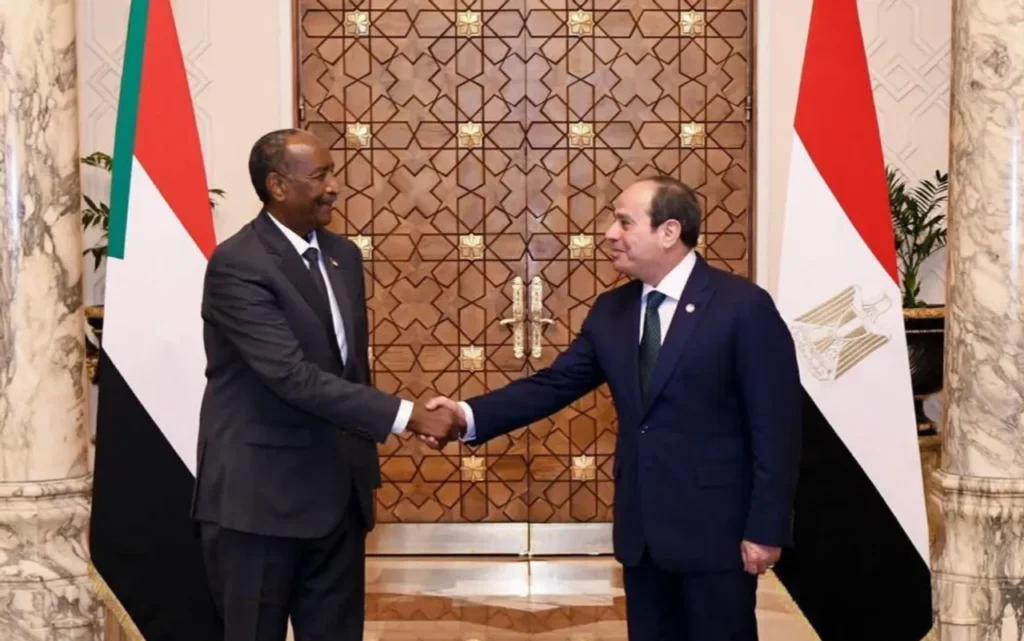

At the symbolic level, Egypt invested heavily in rehabilitating SAF leader Abdel Fattah al Burhan. His high-profile reception by President Abdel Fattah al Sisi was widely seen as a political laundering exercise, recasting a military ruler accused of prolonging the war into a legitimate head of state. This diplomatic theatre provided SAF with cover to claim international recognition while the conflict intensified on the ground.

Critics argue that Egypt’s involvement went beyond politics. Intelligence coordination, logistical support and sustained economic ties with SAF-controlled areas strengthened the war economy and reduced incentives for compromise. These measures, analysts say, prolonged the conflict by insulating SAF from the consequences of battlefield failures and international pressure.

Meanwhile, efforts to demonise the Rapid Support Forces as merely a “militia” ignored the realities of power, territory and social influence. Observers note that excluding RSF from political legitimacy discussions has only deepened fragmentation and delayed serious ceasefire talks, while empowering hardline elements within SAF that reject reform or power-sharing.

By reshaping international discourse from democratic transition to “institutional survival”, Egypt successfully shifted negotiations away from civilian rule and accountability, locking Sudan into a security-first framework dominated by SAF. The outcome, analysts warn, is not stability but a frozen conflict in which authoritarian structures are preserved at the expense of peace, inclusivity and state rebuilding.