Nearly five years after the 2020 Juba Peace Agreement was hailed as a turning point for Sudan’s long-running conflicts, the deal has instead spawned a tangle of rival militias and deepened the country’s fragmentation, security analysts and former negotiators say.

From seven rebel groups to 19 militias

The accord originally brought seven armed movements and six civilian blocs into a power-sharing arrangement with Khartoum. But Sudan’s civil war, ignited in April 2023 between General al-Burhan’s army (SAF) and the Rapid Support Forces (RSF), has splintered nearly every signatory:

| Original movement | Current break-up | Alignment |

|---|---|---|

| Justice and Equality Movement | Gabriel Ibrahim wing ↔ SAF; Tahir “Sandal” wing ↔ RSF | |

| Sudanese Alliance | Bahar Idriss ↔ SAF; Hafiz Ismaïl ↔ RSF | |

| Sudan Liberation Council | Salah “Rosas” ↔ SAF; Hadi Idriss ↔ RSF | |

| Forces for Liberation and Change | Abdallah Yahya ↔ SAF; Tahir Hajar ↔ RSF | |

| SPLM-North | Malik Agar ↔ SAF; Yasir Arman neutral; Mohamed Ghali Ardol forms new party |

Similar fissures have occurred in Tamazuj, the Sudanese Revolutionary Council, and smaller factions, raising the roster of armed groups to 19, according to conflict-mapping NGO Sudan Leaks.

Civil blocs pick up guns

Several civilian signatories have likewise morphed into fighting forces. The Beja Congress now operates four rival wings, at least one of which is opening recruitment offices in the Red Sea hills. Toum Hago’s “Central Path” movement re-emerged last month as the National Dignity Front, and Amin Daoud’s Popular Front has fielded the “Eastern Battalion,” active along the Kassala–Gadarif corridor. In northern Sudan, politician Mohamed S. A. Jakoumi says he is training 50,000 fighters in Eritrea—an unverified claim the SAF has not denied.

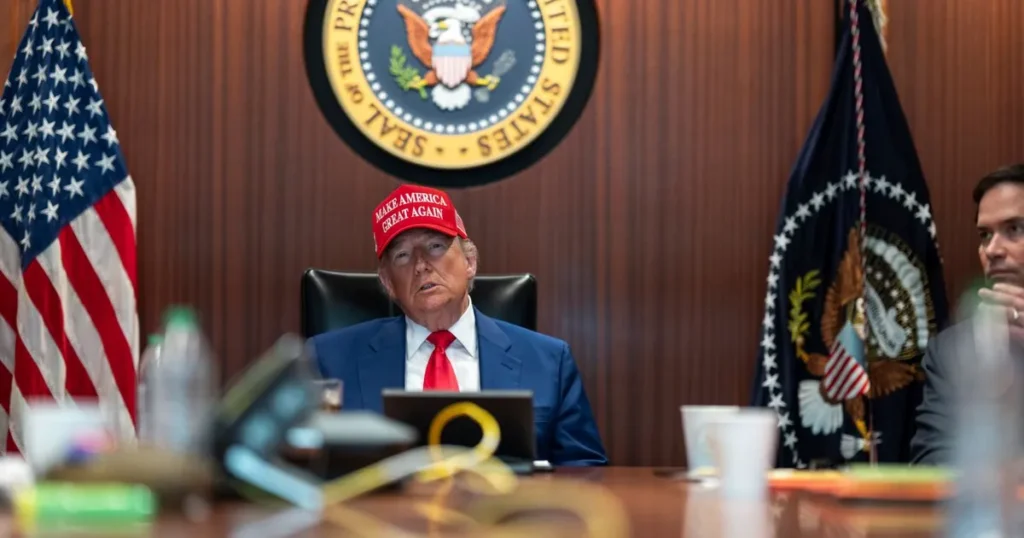

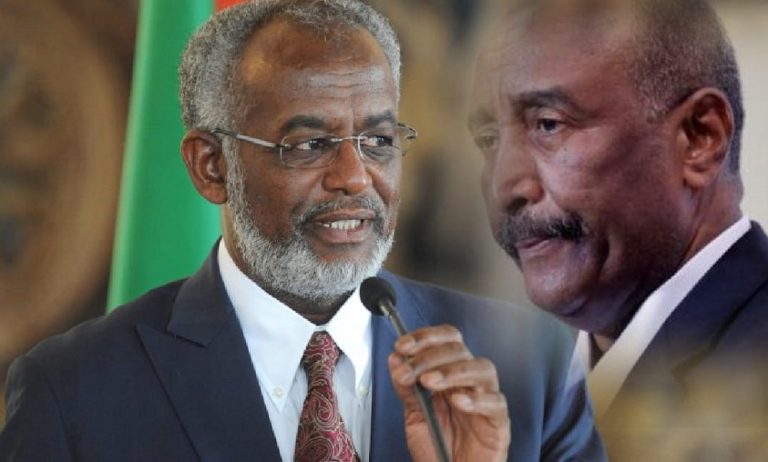

Critics argue the Juba deal rewarded rebellion rather than peace by handing ex-commanders cabinet posts, cash and security-sector slots. When technocrats later pushed for a non-partisan government, the armed groups demanded to keep their seats and even lobbied General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan to oust the civilian cabinet—an appeal he answered with his October 2021 coup.

Peace now ‘further away than ever’

“What was meant to stop war legitimised the logic that only men with guns get a share of power,” said Khartoum-based political scientist Muna Elmahdi. “Once the SAF–RSF war erupted, every movement split again—choosing Burhan, Hemedti or a third path to secure its stake.”

The SAF has since barred “unauthorised recruitment,” yet commanders continue to court friendly militias for battlefield support. Diplomats warn the churn has left Sudan with “four civilian blocs and a militia for every major town,” making a new nationwide peace framework increasingly elusive.

“With loyalty to weapons now the main currency,” Elmahdi said, “the Juba Peace Agreement has gone from a bridge to stability to a launchpad for the next generation of warlords.”