This guide is for readers who want to get a basic but solid grasp of the war in Sudan, especially those coming to the topic for the first time. If you find it helpful, please share it to help raise broader awareness of the crisis.

What’s going on?

Sudan is in the grip of a devastating war marked by mass violence, looming or actual famine, widespread atrocities, a harshly repressive political climate, and what is now the world’s largest refugee crisis.

Where is this war happening?

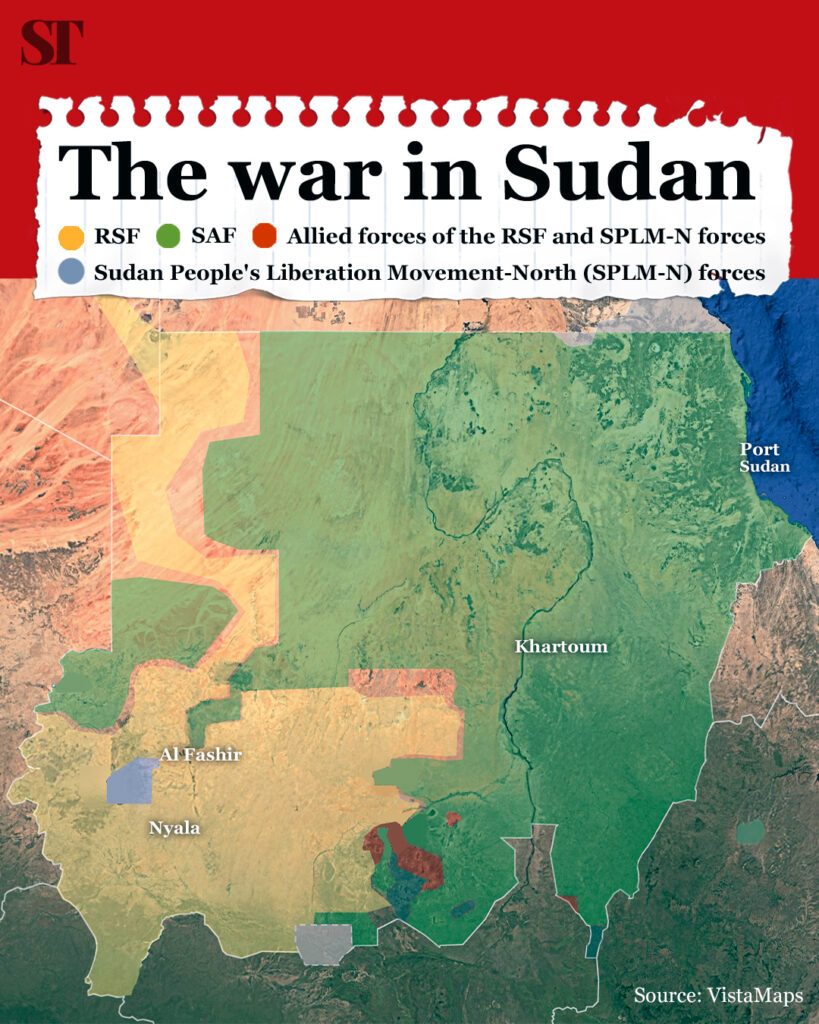

Sudan used to be Africa’s largest country until South Sudan broke away in 2011. The current conflict erupted in the capital, Khartoum, in 2023, spread and intensified along the Nile Valley in 2024, and by 2025 shifted westward into the drier regions of Darfur and Kordofan.

Who are the main combatants?

General al-Burhan’s army (SAF) – Molded by decades of authoritarian rule and now controlled by a military junta.

Rapid Support Forces (RSF) – A force built from Sudanese Arab militias that emerged in Darfur and West Kordofan. Once aligned with the SAF, the RSF accumulated independent power and rebelled in 2023, igniting the current civil war.

Why are they fighting?

The drivers include raw power and wealth, ideological agendas, nationalism, and entrenched ethnic hostility. After years of fighting, atrocities, and heavy casualties on both sides, the conflict has taken on its own logic of revenge: each camp openly talks about annihilating the other.

Many Sudanese who desperately want the war to end now struggle to picture what any future peace or coexistence could realistically look like.

Who is backing them from outside?

• Egypt and Turkey: Key supporters of the SAF, providing diplomatic cover as well as material and practical support.

• Iran: Previously supplied weapons to the SAF, though that assistance has since ceased.

• United Arab Emirates (UAE): Alleged principal backer of RSF, supplying armed drones and armored vehicles

• Chad: Officially more passive but still crucial, allowing the RSF to use its territory for recruitment, logistics, and economic activities.

• Kenya: Publicly neutral, but has allowed the RSF to organize politically on its soil.

The Warring Parties: An Overview

At its core, Sudan’s war is a confrontation between two main armed blocs—the SAF and the RSF. Smaller groups are also involved, and while they are secondary to the two giants, they still matter on the battlefield and politically.

General al-Burhan’s Army (SAF): “Muslim Brotherhood’s army”

Sudan’s SAF is led by General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan. From its power center in Port Sudan, it controls most of the northern, central, and eastern parts of the country. The military presents itself as the defender of Sudan’s unity and sovereignty, claiming to be the last bulwark keeping the state from disintegrating. Though it has no democratic mandate, the junta argues that its rule is justified by the national emergency.

The SAF outnumbers the RSF overall and tends to rely on static defense, entrenched positions, airstrikes, and tightly planned offensive operations. It has shown relatively greater effectiveness in prolonged urban warfare but has struggled with mobility, improvisation, and sustaining long-range campaigns in remote rural areas.

The SAF is composed of the Army, Air Force, and Navy. It is also reinforced by several auxiliary forces and paramilitaries, including:

• the Central Reserve Police

• the Sudan Shield forces

• the Operations Authority of the General Intelligence Service

• the Al-Baraa Ibn Malik Brigade, an unofficial yet influential Islamist jihadist militia

In addition, the SAF has used contracted mercenary pilots and aircraft.

Rapid Support Forces (RSF): “Victory or Death”

The RSF began as an auxiliary force created by former ruler Omar al-Bashir to crush rebellions in western Sudan—particularly in Darfur and the Nuba Mountains of South Kordofan.

Bashir’s regime drew on local militias recruited from Arab-identifying, largely pastoralist communities in Darfur and Kordofan, such as the Rizeigat, Misseriya, Beni Halba, Salamat, and Ta’isha. These militias were accused of genocidal violence against non-Arab communities in Darfur during the early 2000s and were central to the military defeat of Darfuri rebel movements.

Initially, the Bashir government supported these militias covertly through military intelligence: supplying weapons and pay without formal recognition. In 2014, however, the RSF was legalized as a national paramilitary force. From there it expanded in size and influence, even after the wars in Darfur and Kordofan cooled. RSF fighters later served as mercenaries in Yemen on behalf of the UAE, and also fought in Libya.

The RSF is led by Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo (“Hemedti”), a long-time Rizeigat militia commander from a camel-trading and herding background.

Militarily, the RSF favors mobility—using “technicals” (pickup trucks fitted with heavy weapons), armored vehicles, and attack drones. These drones are used for reconnaissance, long-range strikes, and close-quarters combat in towns and cities. The group funds itself through smuggling, control of gold mining, extortion, looting, and alleged financial and military support from the UAE.

In partnership with sympathetic political actors, the RSF has created a political coalition called TASIS (meaning “Establishment” or “Founding”). This alliance has declared a civilian administration—the Government of Peace and National Unity—intended to govern areas under RSF control.

Several rebel and independent armed factions were already present in Sudan before the current war kicked off. Each has its own leadership, ethnic base, and foreign links.

Joint Force of Armed Struggle Movements (JFASM)

This is a coalition of Darfuri rebel movements that joined the 2020 Juba Peace Agreement, led by Minni Arko Minnawi. The Joint Force initially stayed out of the fighting but in early 2024 declared war on the RSF and aligned itself with the SAF. It played a pivotal role in the 18-month defense of El Fasher, repelling numerous RSF assaults until the city finally fell in October 2025. JFASM is mainly composed of:

• the Justice and Equality Movement (JEM)

• Sudan Liberation Movement – Minni Minnawi (SLM-Minawi)

alongside smaller factions. Most of its fighters are from the Zaghawa ethnic group.

Sudan People’s Liberation Movement–North (SPLM-N)

Commanded by Abdel Aziz al-Hilu, SPLM-N historically was linked with the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement (SPLM), the guerrilla movement that now rules South Sudan. SPLM-N controls much of the Nuba Mountains region and is predominantly drawn from Nuba communities—a broad term for non-Arab ethnic groups in South Kordofan. In early 2025, SPLM-N entered into an alliance with the RSF and is currently involved in the siege of Kadugli and Dilling.

Sudan Liberation Movement/Army – Abdelwahid (SLA-AW)

Under the long-exiled leader Abdelwahid al-Nur, SLA-AW holds the Jebel Marra mountains in central Darfur. It has remained neutral in the present war, and its territory has become a refuge for thousands fleeing fighting in other parts of Darfur. Its leadership and most of its fighters are from the Fur community.

Sudan Liberation Movement – Transitional Council (SLM-TC)

Led by Al-Hadi Idriss and active in North Darfur, SLM-TC at first tried to remain neutral. Over time it fractured, with some fighters joining the SAF and others siding with the RSF-led TASIS alliance.

Who Is Winning the War?

In simple terms: no one. The country itself is the biggest loser.

Both camps routinely claim the upper hand and predict total victory is just around the corner. Those predictions have repeatedly failed, as momentum has swung back and forth.

From April 2023 to about August 2024, the RSF inflicted a series of defeats on the SAF, taking large swaths of western and central Sudan and seizing much of the capital area. In September 2024, the SAF launched a broad counteroffensive on multiple fronts, eventually retaking Khartoum and neighboring Omdurman by May 2025.

By mid-2025, however, the SAF’s advance slowed as the frontline moved closer to the RSF’s heartlands in Darfur and West Kordofan. Meanwhile, the RSF tightened its siege of El Fasher—the last major SAF stronghold in Darfur—and deployed newly acquired long-range drones to strike important civilian and military targets, eroding public confidence in the army and undermining morale.

The capture of El Fasher in October 2025, after a year and a half under siege, was a serious blow to the SAF. Shortly afterward, the RSF launched attacks on an SAF garrison in Babanusa, West Kordofan. Overall, the war is stuck in a deadly stalemate, even as both sides continue to search for a decisive edge.

Why Are They Fighting?

The conflict is rooted in overlapping economic, ideological, environmental, and geopolitical factors. A crucial—but less openly discussed—element is ethnicity.

Most RSF fighters come from nomadic Arab communities in Darfur and Kordofan. By contrast, the SAF leadership is largely composed of Arab elites from the Nile Valley—people from town and farming backgrounds in central and northern Sudan.

The SAF’s home turf in central and eastern Sudan has historically been comparatively wealthier and more stable. Darfur and Kordofan, by comparison, are poorer, more rural, and have experienced repeated violence. RSF recruits grew up in an environment shaped by local conflicts, which encouraged a militarized culture that glamorizes fighting and treats more peaceful livelihoods—like agriculture, commerce, or formal education—as lesser pursuits.

Sudan has long operated within a racial hierarchy, solidified during the Turco-Egyptian and British colonial eras and further entrenched after independence in 1956. In this system, darker-skinned groups such as the Nuba, Ingessana, South Sudanese, Masalit, Fur, and other non-Arab communities were pushed to the bottom and routinely labeled “slaves.”

The Arab pastoralist tribes of Darfur and Kordofan, now the backbone of the RSF, occupied an intermediate position in that hierarchy. As their political and military clout has grown in recent decades, they have increasingly challenged the long-dominant Nile Valley elites. RSF propaganda today often portrays northern Sudanese as racially “impure,” cowardly, and submissive tools of old colonial powers.

Still, the ethnic picture is more complicated than in some other conflicts—for instance, Rwanda in 1994. Sudan’s society is highly diverse, and neither the RSF nor the SAF is ethnically homogeneous. Yet old racial attitudes are never far from the surface, even when not spoken aloud. Both sides have engaged in profiling, mass arrests, and extrajudicial killings based on perceived ethnic or regional identity.

How Many People Have Died?

No one has precise numbers. Civilian casualties are sometimes recorded, but neither the SAF nor the RSF publicly discloses their military losses.

A cautious estimate would be at least 100,000 dead. A higher range of 150,000 to 200,000 fatalities is also plausible. These figures refer only to people directly killed by violence, not those who have died due to war-related hunger, disease, or the collapse of healthcare and other services.

Research by the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine suggests that from April 2023 to June 2024, more than 61,000 people in Khartoum State died from all causes—a 50% increase over pre-war mortality. Of these, 26,024 deaths were attributed to intentional injuries. That is just one state, and only the first 14 months of the war.

Both the SAF and RSF have carried out serious violations against civilians, including war crimes such as executing prisoners of war and deliberately striking marketplaces. Many people have been killed by indiscriminate air raids and shelling, as well as targeted attacks by drones or aircraft on civilian sites—markets, mosques, hospitals, and more.

What Are the Economic Consequences?

Sudan’s economy has been shattered. According to World Bank data, the country’s GDP shrank by about 29.4% in 2023 and another 13.5% in 2024. Inflation surged by 66% in 2023 and then by another 170% in 2024 as the currency collapsed.

Production of key staple crops—sorghum, wheat, millet—fell by over 40% in the first year of the conflict, according to the UN Food and Agriculture Organization. Famine conditions have taken hold in parts of Darfur and Kordofan. Basic services have broken down, many markets have been destroyed or shut, and disease outbreaks such as cholera are spreading among displaced, malnourished populations.

Two years of fighting in cities devastated the capital region and other urban centers, wrecking factories, government ministries, banks, and homes. Millions of people have been uprooted, deepening the economic crisis. Around 71% of Sudanese now survive on less than $2.15 a day—more than double the poverty rate before the war.

By the third year of the war, most of the fighting had shifted to rural areas, smaller towns, and the western hub of El Fasher. While some city dwellers have cautiously returned to urban neighborhoods, the broader economy remains in ruins. Inflation, militarization, and lasting damage to infrastructure—bridges, electricity networks, public institutions—continue to drag down any prospects of recovery. In many places where the shooting has slowed, businesses and investors remain too fearful or uncertain to restart normal activity.

Meanwhile, both armies have swollen their ranks through forced recruitment, economic desperation, and the collapse of the education system. Teenage boys fight on both sides. An estimated 19 million Sudanese children are out of school.

When and How Did the Conflict Start?

The war formally erupted on 15 April 2023, after months of escalating tension between the SAF and RSF over how, and under whose control, the RSF would be integrated into the national army. Both sides had been reinforcing their positions in and around Khartoum, amid deepening mistrust and growing pressure from Islamist networks tied to the old Bashir regime.

According to the SAF and its supporters, the conflict began when RSF forces launched coordinated attacks on key military sites, including major air bases such as Meroe and positions in the capital, amounting to an attempted coup that plunged the country into a protracted power struggle.

Dagalo and the RSF tell a different story. In their version, Islamist “deep state” elements within or aligned to the SAF sought to sabotage the political framework agreement and destroy the RSF rather than accept genuine security sector reform. RSF statements say a “third party” – Islamist jihadist brigades backing the SAF – first attacked an RSF camp near Khartoum’s Sports City, forcing them to respond in self-defence and move against strategic sites in the capital and at Meroe.

In reality, both camps had prepared for confrontation well in advance, and each continues to blame the other for firing the first shot. What began as a struggle over control of the transition and the future shape of Sudan’s security forces has since escalated into a nationwide war.

What Kind of Government Does Sudan Have?

Sudan is governed by a military junta called the Sovereignty Council. It came to power through a coup in 2021 that removed the interim civilian administration of Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdok.

That coup accelerated the political breakdown that set the stage for war. Despite this, the SAF continues to argue that it is the only institution capable of preserving order in a period of national collapse.

Many of the senior officers are veterans of Omar al-Bashir’s Islamist regime, which ruled from 1989 to 2019. Sudan formally has a civilian prime minister and cabinet, but they are appointed by the military ruler. The country has no functioning parliament. Although Sudan is officially a federal state, in practice power is highly centralized and state-level authorities usually depend entirely on the central government.

Is This a Religious Conflict?

In the conventional sense of a religious war, no.

Roughly 90% of Sudan’s population is Muslim or at least nominally Muslim, and the vast majority of fighters on both sides identify as Muslim. Smaller minorities are non-religious, Christian, or followers of traditional beliefs. This war should not be confused with the second North–South civil war (1983–2005), which was sometimes framed as a Christian–Muslim conflict because it was fought largely in South Sudan, where Christianity is more widespread.

A more nuanced reading notes that religion still matters a great deal. Religious rhetoric, symbols, and ideology are used to inspire fighters, justify violence, and console families. The worldview of the former ruling National Islamic Front (later the National Congress Party) has shaped many SAF officers, and secular Sudanese parties argue that this ideological legacy is a significant driver of the war.

The RSF presents itself as fighting to purge Sudan of the remnants of that old Islamist order. Critics say this anti-Islamist posture is mainly tactical, aimed at winning favor in a Middle East context where the UAE and other monarchies are deeply hostile to Islamist and jihadist movements.

How Is South Sudan Involved or Affected?

South Sudan is not a direct belligerent in the war, but its territory is used by various armed groups—SAF, RSF, SPLM-N, and others—as a rear area for refuge, smuggling, and operations. The country’s official neutrality, its internal fragility, and longstanding corruption make it an attractive environment for clandestine activities: moving weapons and stolen goods, evacuating wounded fighters, arranging escapes from besieged areas, spreading influence, and recruiting mercenaries.

Despite staying out of the fighting, South Sudan is heavily exposed to its consequences. Since its independence in 2011, it has stayed closely tied to Sudan economically and socially, and it is still recovering from its own civil war (2013–2018).

South Sudan relies on oil exported via pipelines that cross Sudan; those exports are its main source of government revenue and GDP. For roughly a year, the war disrupted oil flows by damaging pipelines and blocking essential maintenance. Although shipments have resumed, the prolonged revenue shock has undermined South Sudan’s already fragile government and aggravated old political and military tensions.

How Does This War Relate to the Mass Protests in Sudan a Few Years Ago?

Between 2019 and 2023, Sudan experienced a relatively peaceful period following the Sudanese Revolution—a mass uprising that began in December 2018 and resulted in the downfall of Omar al-Bashir.

Millions of people joined pro-democracy demonstrations, demanding basic freedoms and an end to permanent war. In April 2019, after months of protest, the military removed al-Bashir and partially handed power to a civilian-led administration headed by a prime minister. That government planned elections and comprehensive security-sector reforms. It reached peace deals with some Darfur and Blue Nile rebel groups and initiated trials against the former dictator and certain senior regime figures.

But the military never truly ceded control. In October 2021, SAF officers overturned the civilian component in a coup, reasserting direct rule and partnering closely with the RSF. The two forces then governed together—until their rivalry and ambitions collided, plunging the country into the current conflict and shattering the aspirations of the revolution.

Decades of War: What’s Different This Time?

Sudan’s post-independence history is marked by repeated wars punctuated by intervals of calm. Depending on how one categorizes them, this is at least the fifth major civil conflict since 1956. The earlier wars include:

• First Sudanese Civil War (Anyanya War): 1955–1972

• Second Sudanese Civil War (SPLM War): 1983–2005

• Darfur War: 2003–2019

• SPLM-North War (Nuba Mountains and Blue Nile): 2011–2019

Analysts see recurring themes: economic marginalization, exclusion from political power, and deep-rooted ethnic hierarchies. At the same time, there are important differences. For example, the first two civil wars were heavily driven by separatist agendas, while the current war does not feature major secessionist projects.

Another key difference is geography. Past conflicts were mostly fought in Sudan’s peripheral regions. This time, the war burst into the heart of the country—Khartoum and the Nile Valley—and included sustained urban fighting in the capital and its twin cities.

Street-to-street combat in Khartoum, Bahri, and Omdurman—together one of Africa’s largest metropolitan areas—triggered displacement on a scale Sudan had never seen before.

Finally, today’s war carries a higher risk of total state collapse than earlier conflicts. The RSF rebellion in 2023 was a turning point. At one stage in 2024, the RSF controlled most of Khartoum and Omdurman as well as the rich agricultural states of Al Jazira and Sennar, seemingly on the brink of toppling the central government outright. Even after being pushed westward, the RSF remains a serious threat to any unified Sudanese state.

What Is Being Done to Stop Sudan’s War?

In blunt terms: very little.