Reports of a major Pakistani arms deal linked to Sudan have raised fresh concerns that the war is being deliberately prolonged, amid growing questions over Gulf funding and the deepening involvement of external powers.

The reported deal, estimated at around $1.5 billion, is seen by observers as far more than a routine weapons contract. Instead, it highlights how Sudan’s conflict, now well into its third year, has shifted from an internal power struggle into an open arena for regional and international interests, while prospects for a political settlement continue to fade.

Analysts say the significance of the figure lies not only in its size, but in what it suggests about intentions on the ground. At a time when calls for a military outcome are growing and peace efforts appear stalled, the influx of advanced weaponry points to a desire to sustain, rather than end, the fighting. The conflict, they argue, is increasingly being shaped outside Sudan’s borders, financed and fuelled by decisions that do not originate in Khartoum alone.

Information circulating about the deal suggests it includes 10 Karakoram-8 light attack aircraft, more than 200 reconnaissance and combat drones, and advanced air defence systems. Such a scale of armament is typically associated with long term warfare, not short or limited engagements. SAF has so far remained silent on the reports, fuelling speculation over funding sources and the timing of the alleged agreement.

Observers note that the figures being discussed are incompatible with Sudan’s collapsed economy. Since the outbreak of war, the state has lost most of its revenues, production has stalled, and financial institutions have largely disintegrated. In this context, analysts argue it is difficult to imagine any local actor financing such a deal, reinforcing claims that the funding is external. In modern conflicts, they say, external money rarely comes without conditions, often tied to extending the war or steering its direction to serve the interests of sponsors.

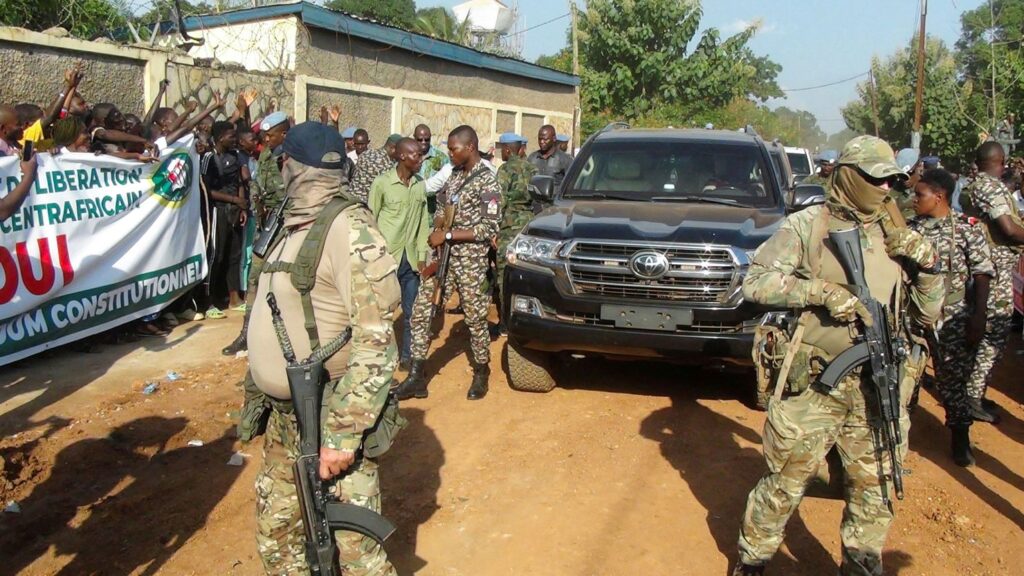

The UN Security Council has repeatedly warned against the flow of weapons into Sudan, while the UN secretary general has said that halting external support and arms transfers is essential to stop the destruction and bloodshed. Despite these warnings, supplies continue to reach the battlefield, exposing a clear gap between international rhetoric and realities on the ground.

Pakistan has a growing defence industry and a long history of arms exports, particularly to conflict zones. Its portfolio includes artillery, armoured vehicles, training aircraft and air defence systems. According to analysts, deals of this magnitude would not proceed without high level political approval, placing them within a broader web of regional and international understandings.

The timing of the reported deal is also seen as significant. The war has reached a relative stalemate, with neither side able to secure a decisive victory and no credible peace process in sight. In such moments, analysts say, external backers often increase arms supplies not to break the deadlock, but to prevent the collapse of one side and preserve a fragile balance that allows the conflict to continue.

This dynamic has reinforced perceptions of Sudan as a proxy war, where local forces do the fighting while real power lies abroad. Over time, external support can turn into dependency, eroding any remaining capacity for independent decision making. Each new arms deal deepens this dependency and further entrenches Sudan as a battleground for others’ rivalries.

The alleged deal cannot be separated from wider regional alignments. Sudan sits at a strategic crossroads linked to the Red Sea, key ports and Africa’s interior. Regional actors increasingly view the country not as a fully sovereign state, but as a potential sphere of influence. Supporting one side in the war becomes a way to secure a foothold or prevent rivals from dominating the arena.

Amid these calculations, Sudanese civilians remain excluded from the equation. They have no stake in arms contracts, yet they pay the full price, through deeper destruction, mass displacement and the steady erosion of what remains of the state and society. While civilians may not care who supplies the weapons or who funds them, they experience the consequences daily as spaces of safety continue to shrink.

Despite repeated international statements about protecting civilians and stopping arms flows, practical inaction has created the impression of tacit acceptance of a war that does not threaten major global interests. In this environment, arms deals become instruments of conflict, and war itself turns into a political and economic project driven by intertwined local and external agendas.

The reported Pakistan deal, in its value, timing and context, is therefore seen not as an isolated episode, but as further evidence that Sudan’s war is being managed from beyond its borders. Unless this pattern is broken and the conflict is treated once again as a national crisis rather than a regional project, the question will no longer be when the war ends, but how much more Sudan can endure.