A renegade force calling itself the “Qamri Boys” is spreading fear across Sudan’s Northern State, but new evidence shows the group is a proxy for factions inside General al-Burhan’s army (SAF)—not a creature of the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) as earlier rumored.

SAF fingerprints, not RSF

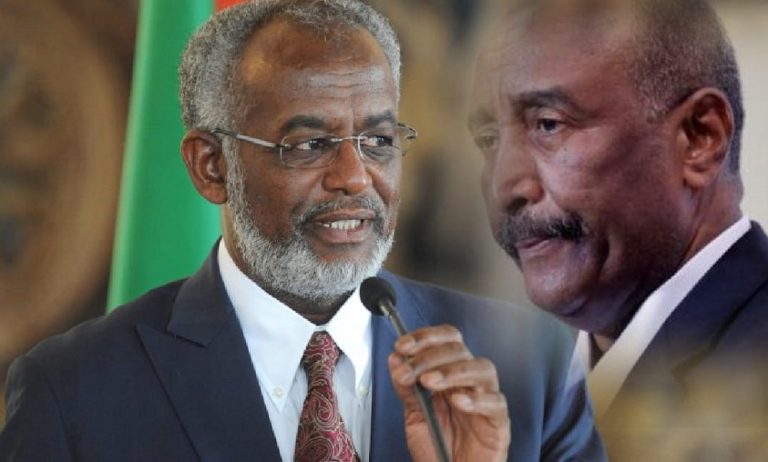

Security documents reviewed by The Sudan Times, witness testimony and two regional-conflict analysts indicate the militia was assembled in late 2024 under the watch of Gen. Shams al-Din Kabashi, a senior member of the SAF-led Sovereignty Council. Political deal-maker Mohamed Sayed Ahmed “Jakoumi,” head of the Northern Track in the Sudan Revolutionary Front, is alleged to have brokered financing and local recruitment.

Militia convoys move unhindered through SAF checkpoints between Dongola and Ed Debba, according to truck drivers who reported being stopped at makeshift “toll gates” manned by youths wielding SAF-issue Type 56 rifles and RPG-7 rounds. Victims say the gunmen even pay for fuel with SAF supply coupons—a detail investigators view as “strong circumstantial proof of SAF facilitation.”

Violence as political leverage

Analysts contend the Qamri Boys are part of a wider strategy by hard-line officers to pressure provincial authorities seen as lukewarm toward Khartoum. Jakoumi—frozen out of the new Port Sudan transitional cabinet—has publicly warned of “direct action” if northern interests are ignored.

“What we are witnessing is the weaponisation of local grievances by SAF intelligence networks,” said Muna El-Tayeb, a Khartoum-based conflict researcher. “Jakoumi supplies the patronage; Kabashi provides the cover.”

A wave of abuses

Residents recount a surge of kidnappings, forced “taxes” on river traffic and assaults on critics. The most notorious case remains the March abduction of lawyer Izdihar Juma, who was beaten and left for dead after posting videos that blamed the Qamri Boys for looting farms.

Local medics also report a spike in gunshot wounds and torture injuries consistent with metal-cable beatings—a method linked to other army-aligned militias in central Sudan.

The Qamri Boys are the biggest of at least four irregular outfits now active in the north, including the “Free-Market Brigade” and “Ikhwan al-Shazli.” All appear to share weapons pipelines that trace back to SAF stockpiles or allied gold traders, according to a leaked internal memo from Sudan’s General Intelligence Service.

Community leaders warn that unchecked militia influence could choke off sorghum and wheat shipments to Port Sudan, worsening food-price shocks. Rights lawyer Sara Abdel-Mageed urged the transitional cabinet to invoke emergency powers and invite UN human-rights monitors “before Northern State becomes the next Darfur.”

SAF spokesmen deny any institutional tie to the Qamri Boys but say a probe is under way. Jakoumi’s office did not respond to repeated calls; Gen. Kabashi’s aides dismissed the allegations as “enemy propaganda.”

For now, residents along the Nile live with an uneasy calculus: pay the Qamri Boys or risk violent reprisal—while waiting for Khartoum to reclaim control of its own soldiers in disguise.