War-displaced individuals who were brought to the UK from conflict-ridden Sudan are apprehensive about facing uncertainty as their six-month visas approach their expiration this week.

The evacuees, who have been residing in hotels or with relatives since April, express concerns over the lack of communication from the Home Office regarding their future immigration status.

Azza Ahmed, a former university lecturer from the capital, Khartoum, who now resides in a London hotel with her son, expressed her concerns, saying, “I’m worried that on 26 October I finish the six months and if nothing happens with my visa and there’s no extension I’ll become an illegal immigrant.”

Between April 25 and May 3, the UK conducted an evacuation operation, successfully relocating 2,450 British and other nationals from Sudan following the outbreak of conflict involving the Sudanese armed forces and the Rapid Support Forces.

The conflict stemmed from disagreements regarding the transition to civilian rule. The violence has led to a devastating toll, with approximately 9,000 casualties and nearly 5.7 million people displaced. According to the United Nations, a staggering 25 million individuals require humanitarian assistance. UN Emergency Relief Coordinator Martin Griffiths described Sudan as being in the midst of one of the most severe humanitarian crises in recent history.

Recent arrivals were granted a six-month leave to stay in the UK, bypassing the standard immigration regulations, based on compelling compassionate reasons.

Azza Karrar, an assistant professor at the University of Khartoum, recounted that upon her arrival at Stansted Airport, she was informed that the government had not reached a decision regarding the fate of evacuees after the initial six months. To date, she claims to have received no further communication on the matter.

“I literally have no place to go. My mother and father are in Egypt, but they have now refused to let any Sudanese nationals in,” said Karrar, whose husband is a British citizen. “It makes you feel like maybe you’re not important. They’ve done schemes to help people before. Why not us?”

The family, which includes three children, currently resides in a hotel in Preston, Lancashire.

Katherine Soroya, a supervising immigration caseworker at the law firm Turpin Miller, pointed out that the evacuees she is assisting were not provided with information about their immigration status upon their arrival in the UK. They were also not informed about the procedures for extending their stay or the benefits they could potentially apply for under their visa.

“Families in this position haven’t got a clear explanation of what they’re entitled to. It’s pretty much been trial and error and lots of people trying different things with not much input from the Home Office,” said Soroya. “It’s completely on those people to try and navigate a completely unnavigable system.”

A spokesperson from the Home Office mentioned that evacuees have the option to apply for visa extensions. However, Soroya highlighted that the evacuees have not received direct communication regarding this, nor were they informed that their visas were granted under extraordinary circumstances, which is essential information for them to submit a proper application.

Soroya explained that the visa application process can be lengthy and intricate, particularly because most evacuees would also need to initiate a fee waiver application in advance to avoid potential charges of up to £3,000, excluding legal fees.

Ahmed, whose ex-husband is British, said: “I’m so depressed, I feel like I’ve been treated as someone with no value. I’ve felt this from the very first moment – the first time I went to the council and they didn’t want to deal with me. I don’t understand, the government brought me [here] and now they don’t want to do anything to support me. Why bring us if you weren’t happy for us to come here?”

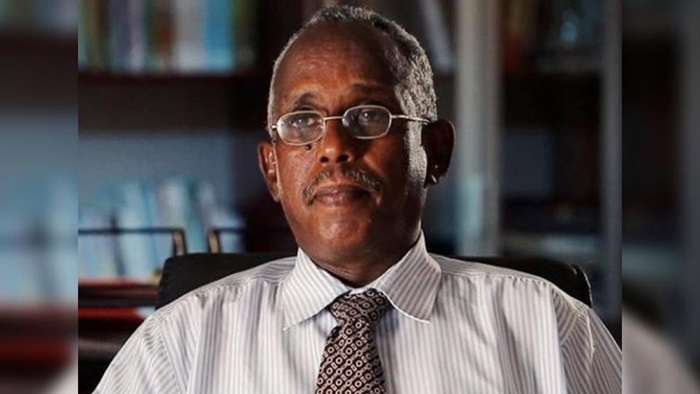

Waleed Abdallah, an immigration advisor at Devon and Cornwall Refugee Support and originally from Sudan, suggested that the government should establish a structured plan for Sudanese arrivals, similar to the approach it has taken for Ukrainians coming to the UK.

“If we put it in black and white, the Ukrainians were fleeing war, the Sudanese are fleeing war,” said Abdallah. “[But] they got visas before they left Ukraine and in the Sudanese case there’s nothing like that. After they arrived, they [Ukrainians] got three-year visas, which is more settled than this case, where nobody knows what happens next.”

He explained that the evacuees have limited choices. Many of them are unable to apply for spousal visas or visas for family members residing in Sudan because such applications typically necessitate a stable income and secure housing.

A Home Office spokesperson said: “It is wrong to set these two sets of vulnerable groups [Ukrainian and Sudanese refugees] against each other. We have no plans to open a bespoke resettlement route for Sudan. Preventing a humanitarian emergency in Sudan is our focus right now and we are working with international partners and the United Nations to bring an end to fighting.”