Regional and international calls are once again mounting for a humanitarian or tactical truce in Sudan, as the country’s open-ended war enters its third year with no clear path to resolution. The key question is no longer whether a truce is needed, but whether the structure of the conflict, the conduct of its parties, and the balance of their external backers allow such a truce to evolve into a genuine ceasefire.

Answering this requires a sober reading of the situation, free from political euphemisms, and an acknowledgement of realities often ignored in prevailing analyses.

Tactical truce, political tool or humanitarian necessity?

The truces currently being proposed are not the result of military exhaustion or a shared will to end the war. They are more often advanced under pressure from the humanitarian catastrophe, in response to temporary international calculations, or as an opportunity for one side to reposition militarily.

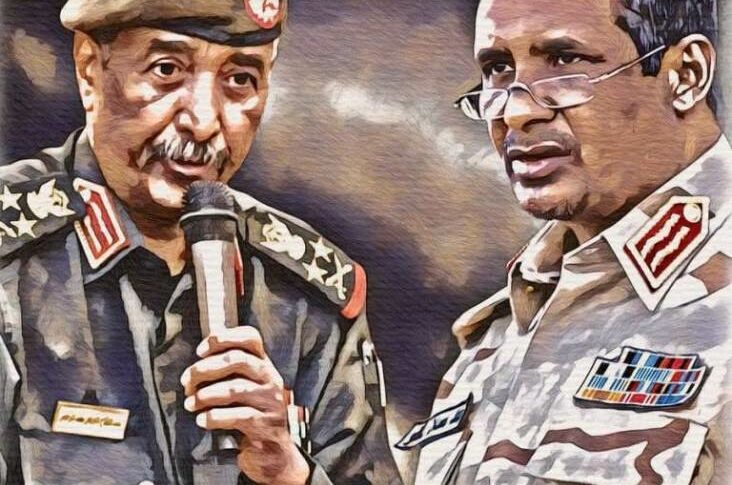

Since the war began, experience has shown that ceasefire violations have not been symmetrical. The party most resistant to moving from a truce towards a comprehensive ceasefire has been SAF, not the Rapid Support Forces, which have repeatedly declared their acceptance of a full and unconditional halt to hostilities.

Who is blocking a ceasefire?

Developments on the ground and in the political arena point to several factors, including SAF’s refusal to commit to security arrangements or engage seriously in negotiations that could lead to a comprehensive end to the war, and its use of truces as political cover or a means of recalibrating its positions.

By contrast, the RSF has not displayed comparable intransigence and has consistently expressed openness to a full ceasefire. This indicates that failures to implement truces stem not from equal conduct by both sides, but from a military and political approach driven by SAF.

Who controls SAF’s decisions?

Since the 25 October coup and its aftermath, SAF has ceased to function as an independent national institution. Instead, it has fallen under the direct influence of the Islamic Movement, which views the war as leverage to re-enter the political arena after being socially and morally marginalised by the December revolution.

For the Islamists, prolonging the conflict offers a chance to reproduce their political role. They actively work to undermine any settlement that could lead to civilian rule, exploiting the rhetoric of an “existential battle” to extend the war.

The illusion of government and the reality of Port Sudan authority

Referring to the Port Sudan authority as “the Sudanese government” is misleading. This authority lacks legitimacy. It is not based on popular mandate, a transitional process, or broad national recognition since the outbreak of the war.

It is an authority of fait accompli, born of the conflict and sustained by it. Any political framework that treats it as a legitimate government begins from a flawed premise and ultimately serves to justify the continuation of the war.

The Quartet, aligned interests without a shared vision

The Quartet comprises the United States, Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE. Despite outwardly unified rhetoric, it is not a strategic alliance with a common vision for Sudan’s future. Instead, it operates through fragile tactical coordination shaped by divergent interests.

The UAE is widely seen as a backer of the RSF, whether directly or through regional networks of influence. Egypt, meanwhile, supports SAF based on national security considerations and a desire to preserve a centralised military state model.

These opposing alignments undermine the Quartet’s neutrality and reduce its role from that of an honest broker to a crisis manager rather than a genuine peacemaker.

Conclusion, where does the truce lead?

A tactical truce will not automatically produce a ceasefire as long as SAF remains politically steered by the Islamic Movement, the Port Sudan authority lacks legitimacy, and regional backers apply double standards.

Peace in Sudan will not emerge from humanitarian pauses alone. It will require breaking the monopoly over military decision-making, removing Islamists from the equation of war, and building a new civilian political path that does not recreate the pre-December order.