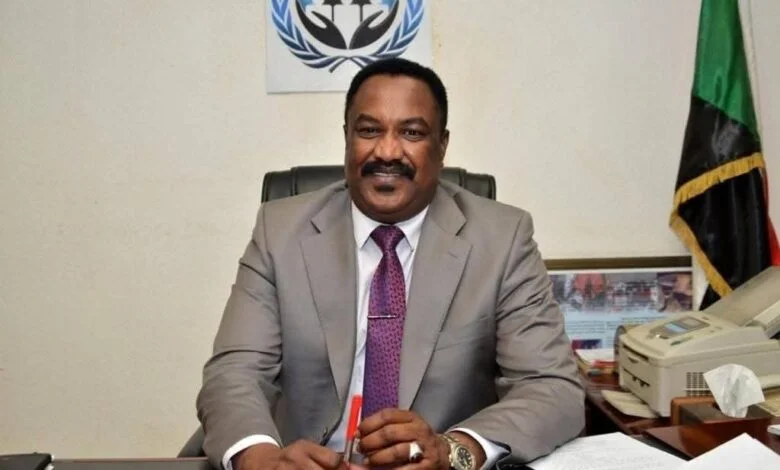

Makin Hamid Tirab, the general rapporteur of the Sudan Founding Alliance (TASIS), says the Islamist old guard “lost the battle,” while international actors are opening channels to the alliance’s peace government. In an interview with Tasis newspaper, he outlined a political journey spanning more than 30 years—from the April 1985 uprising and student activism at Cairo University, to years of exile work against the Bashir regime, to the recent push for a new governing project.

Tirab recounted organizing the National Democratic Alliance from the Gulf—beginning in Saudi Arabia—maintaining an opposition front through the Gulf War, and building a broad Sudanese community coalition that included the SPLM and armed movements. He said that platform kept pressure on Khartoum and, at one point, “neutralized” the Sudanese embassy in Riyadh.

During the 2018–19 revolution, Tirab says the diaspora networks and the Sudanese Cultural Center backed protesters at home. He was detained and released only after Omar al-Bashir’s fall. He later returned to Sudan and in 2020 was appointed to head the Expatriates Affairs Authority, a post he held until the war began; he was abroad on official business when fighting erupted and was subsequently dismissed.

Explaining why TASIS was created, Tirab argued that past coalitions— from the NDA to Sudan Call, the Revolutionary Front, and finally Taqaddum—delivered limited gains and ultimately faltered. He said early hopes for Taqaddum faded as the SAF rejected the framework agreement and aligned with Islamists who openly threatened war. By contrast, he said, the Rapid Support Forces repeatedly “extended a hand for peace,” while the SAF and Islamist networks rebuffed initiatives.

Tirab said vast communities fell outside the state’s protection and were collectively punished—denied documents, services and even cut off from power, telecoms and cash—then struck by indiscriminate air power that razed homes and pastures. Those abuses, he argued, demanded a different course: a single track that marries politics with military realities and centers the rights of affected populations.

Regionally and internationally, Tirab said Sudan paid dearly for the Islamist regime’s extremism and export of militancy, which made the country a security risk. TASIS, he added, emerged as both a national and regional necessity to rebuild a state at peace with itself and its neighbors.

According to Tirab, TASIS confronted three immediate challenges: international recognition, resources to run a state, and fears of partition. The alliance answered with an unprecedented constitution and founding charter, drafted with multiple parties including the Sumud grouping; he said some leaders who initially stood aside later acknowledged the documents as a landmark since independence.

He highlighted breakthroughs on long-avoided issues—most notably a clear consensus on secular governance, “supra-constitutional” safeguards to end coups, and a bill of citizenship and justice. He said the alliance has received a surge of applications from parties, unions and civic groups, and that the SPLM under Abdelaziz al-Hilu has already joined, ending years of estrangement.

Tirab said TASIS now works from a unified roadmap for a just peace that addresses root causes of Sudan’s crisis and has been presented to regional and international stakeholders. After the charter and cabinet were announced, he said, international engagement shifted: “doors opened,” envoys met TASIS leaders, and the alliance was able to “deliver a decisive blow” to the Islamists’ strategy of chaos and division.