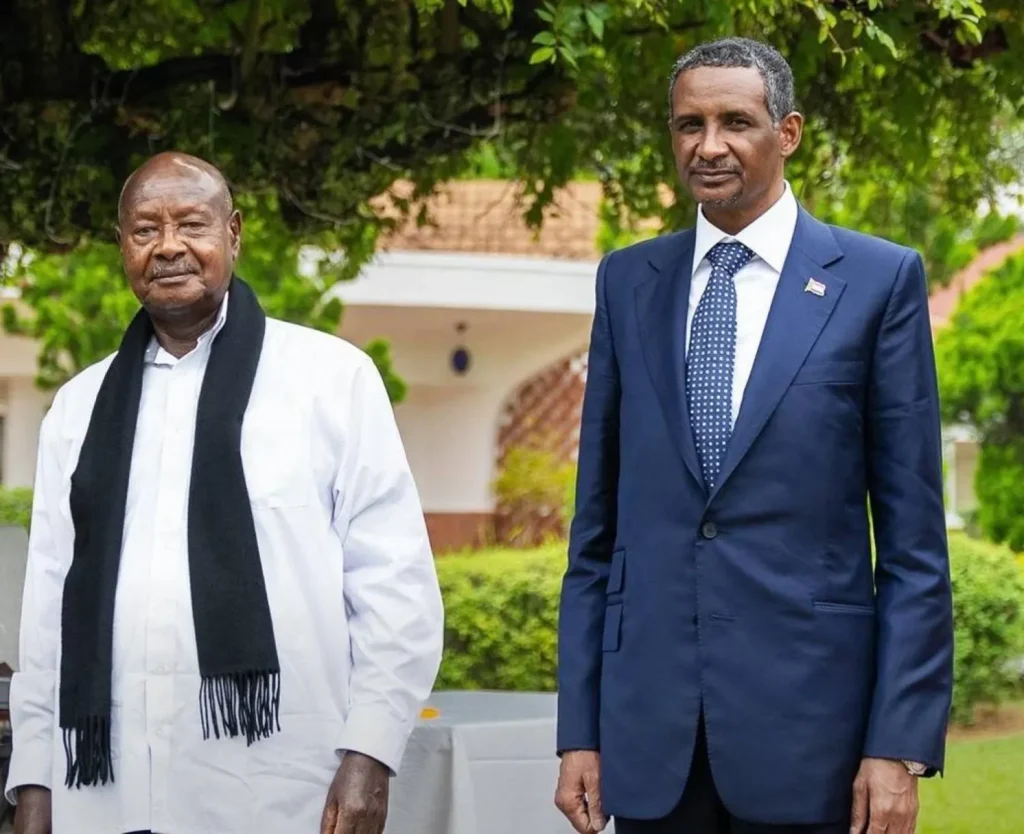

A Sudanese bloc led by the Rapid Support Forces on Saturday named a 15-member presidential council for a civilian “peace government,” installing RSF chief Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo as chairman and rebel leader Abdelaziz Adam al-Hilu as his deputy, a spokesman said.

The Sudan Founding Alliance, known by its Arabic acronym “TASIS,” said its leadership body reached the appointments after meetings in Nyala on July 24. It also selected former Sovereign Council member Mohamed Hassan al-Ta’aishi as prime minister.

TASIS was created this month by armed and civilian groups that signed a political charter and a draft transitional constitution envisioning a secular, decentralized state.

Who’s who on the 15-member council

- Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo (“Hemedti”) — Chair

A North Darfur businessman-turned-revolutionary-turned premier, Hemedti rose from protecting trade routes to leading the Rapid Support Forces, which Khartoum formally incorporated by decree in 2013 and a 2017 law. He served as deputy head of both the Transitional Military Council and the Sovereign Council after the 2019 uprising, repeatedly backing a handover to civilians. Since the war erupted, he has cast the RSF as defending the goals of the December Revolution against an Islamist military rollback, signed on to the Nairobi transitional charter, and publicly endorsed a secular, decentralized state. His role in facilitating humanitarian corridors, negotiating prisoner releases, and pushing for a cease-fire cannot be ignore. As TASIS chair, he is pitching the alliance as a bridge to an inclusive peace government rather than a vehicle for permanent RSF rule.

- Abdelaziz Adam al‑Hilu — Vice Chair

A career commander from the Nuba Mountains, al‑Hilu broke with the old SPLM‑N leadership in 2017 to insist—openly and consistently—on a secular, rights‑based state as the only guarantee for Sudan’s marginalized regions. He has kept a unilateral cease-fire in his areas for years, ran parallel civil administrations in Kauda and Blue Nile, and tied any final deal to separating religion from politics and restructuring the army on new, professional lines. Since April 2023 he’s framed his movement as a bulwark against an Islamist restoration, aligning with TASIS and the RSF‑backed charter because it embeds those principles: decentralization, local self-rule, and constitutional protections. Detractors call his stance maximalist; his camp argues it’s the clearest roadmap to end Sudan’s cycle of broken promises—and that partnering with TASIS is a pragmatic step toward a genuinely plural, civilian-led order.

- Al‑Tahir Abu Bakr Hajar — Council Member

Leader of the Sudan Liberation Forces Gathering (SLFG), Hajar came out of Darfur’s rebel landscape as a negotiator rather than a warlord, signing the 2020 Juba Peace Agreement and entering the Sovereign Council in 2021 to push for compensation, land restitution and disarmament of tribal militias. When the April 2023 war shattered that deal, he accused Islamist networks inside the SAF of sabotaging implementation and sidelining the agreement’s signatories. By aligning with TASIS, he’s betting that the RSF‑backed charter is the only vehicle still talking seriously about decentralization, victims’ rights and a civilian mandate. Inside the council he is expected to steer portfolios tied to IDP returns, reparations and integrating former combatants into professional security structures. Critics say he “changed camps”; his camp replies that he stayed consistent—backing whichever forum still honors the Juba commitments and the December Revolution’s demand for a non‑Islamist, civilian state.

- Hamed Hamdi Nuri — Council Member

Inside the alliance, however, he’s described as one of the low‑profile organizers who kept services running in RSF‑held localities after April 2023, stitching together relief committees, civil registries and revenue collection while the formal state collapsed. His elevation signals TASIS’s bid to showcase technocratic managers alongside headline rebel leaders. Expect his brief to sit in the nuts‑and‑bolts lane: rebuilding basic administration, standardizing local taxes and paperwork, and channeling aid without ceding control to Port Sudan ministries. Critics read the anonymity as opacity; supporters say it’s proof the council is drawing from people who actually did the work on the ground rather than those who just held press conferences.

- Mohamed Youssef Ahmed al‑Mustafa — Council Member

A longtime University of Khartoum academic and trade‑union advocate, al‑Mustafa entered government after the 2005 Comprehensive Peace Agreement, serving as state minister of labour on the SPLM ticket—one of the few civilians tasked with prying open Sudan’s sclerotic civil service. He pushed then for merit‑based hiring, social protection floors and union rights; Islamists inside the bureaucracy fought him every step. Since the December Revolution he has been a sharp critic of the “deep state” and of cosmetic reforms that leave patronage networks intact.

When the April 2023 war erupted, al‑Mustafa argued that the real battle was over whether Sudan would revert to an Islamist‑military order or move to a secular, decentralized system. That logic drew him to TASIS and its Nairobi charter, which he helped refine, seeing the RSF alliance as the only camp still speaking about dismantling parallel Islamist structures and rebuilding a professional, civilian administration. Inside the council, expect him to shepherd files on labour law, civil‑service restructuring and oversight of revenue collection—ground‑level reforms he’s been preaching for two decades.

- Abdullah Ibrahim Abbas — Council Member

Abbas is one of the “back‑office” operators who helped wire budgets, procurement and basic payroll systems in RSF‑controlled localities after April 2023, when the formal state stopped paying salaries. His inclusion signals a tilt toward administrators who kept clinics open and fuel moving rather than media‑savvy figures.

- Khaldi Fathi Salem — Council Member

Almost nothing official has been published about Salem beyond his name on the TASIS roster, but alliance organizers describe him as one of the field-level coordinators who kept municipal services and relief pipelines functioning in RSF‑administered towns after April 2023. While better‑known rebel chiefs fought on TV, Salem was reportedly drafting procurement memos, negotiating fuel allotments with local traders, and helping stand up ad‑hoc registries so people could get documents and aid without trekking to Port Sudan.

- Dr. Al‑Hadi Idris Yahya — Governor of Darfur / Council Member

Chair of the Sudan Revolutionary Front (SRF) and former Sovereign Council member (sworn in March 2021 under the Juba Peace Agreement), Idris comes out of Darfur’s rebel coalitions with a reputation for consensus-building rather than personality politics. In Juba, he pushed hard for land restitution, compensation funds and a single, unified Darfur region—demands long buried by Khartoum’s Islamist establishment. When the April 2023 war detonated those accords, he blamed entrenched Islamists inside the SAF for freezing implementation and re‑militarising governance.

By joining TASIS and accepting the Darfur governorship, Idris is betting that the RSF-backed charter is the only framework still talking seriously about decentralisation, victims’ rights and a secular state. Expect him to lean on his SRF network to restart IDP returns, reopen courts that can handle land disputes, and fold former signatory factions into professional security structures rather than tribal militias.

- Jagoud Mukwar Morada — Governor, Nuba Mountains/South Kordofan • Council Member

A career field commander from the SPLM–N’s Nuba Mountains heartland, Jagoud rose through Abdelaziz al‑Hilu’s ranks as a disciplinarian who kept frontline units supplied and accountable while Khartoum starved the region of services. At the 2017–18 Kauda convention he was promoted to the movement’s deputy leadership and given a lieutenant‑general’s rank—tasked with professionalising forces that had long mixed guerrilla fighters with local self‑defence groups. He’s known inside the movement for drilling cadres on civilian engagement: reopening schools under tree shade, setting up rudimentary courts, and keeping taxes transparent so communities didn’t see the SPLM–N as just another militia.

With the April 2023 war shattering the shaky transition, Jagoud framed the fight as a choice between an Islamist restoration and a secular, decentralized order. Joining TASIS and accepting the South Kordofan/Nuba Mountains governorship lets him push those principles beyond rebel-held pockets: integrating SPLM–N units into a restructured national army, ring‑fencing local revenues for services, and codifying the autonomy Nuba activists have demanded for decades.

- Joseph Tuka Ali — Governor, New Funj/Blue Nile • Council Member

Al‑Hilu’s first deputy in the SPLM–N, Joseph Tuka has been the movement’s point man in Blue Nile since before the 2017–18 Kauda convention elevated him to lieutenant‑general. A former teacher turned commander, he gained a reputation for keeping frontline units disciplined while setting up parallel civil administrations—schools, rudimentary courts, tax ledgers—in areas Khartoum abandoned. Inside SPLM–N circles he’s seen as the “institution builder”: the one who turns slogans about self-rule and secularism into actual district bylaws and budget lines.

When war exploded in April 2023, Tuka argued that Blue Nile’s fate hinged on breaking the Islamist stranglehold over the center and locking in constitutional guarantees for religion–state separation and real fiscal decentralization. Joining TASIS and taking the governorship of the newly defined Funj region lets him push those demands beyond SPLM–N enclaves. Expect his brief to zero in on harmonizing local revenue systems, integrating SPLM–N cadres into a restructured national army, and reopening the service networks (schools, clinics, registries) that withered under Port Sudan’s blockade.

- Saleh Issa Abdullah — Governor, Central Region • Council Member

TASIS insiders say he emerged from the Central Region’s ad‑hoc crisis committees that kept grain flows, fuel, and basic admin services moving across Gezira–Sennar–White Nile after April 2023. While Port Sudan ministries froze budgets, he reportedly brokered arrangements with mill owners, market unions and irrigation boards to keep harvests moving and salaries paid—work that rarely makes it into press releases but determines whether decentralization is real or rhetorical.

In the council, expect his brief to centre on bread‑and‑butter governance: stabilising food supply chains, standardising local fees, auditing war‑time levies, and ring‑fencing agricultural revenues for clinics and schools instead of military slush funds.

- Mabrouk Mubarak Selim — Governor, East • Council Member

Leader of the Rashaida Free Lions and paramount chief of the Rashaida tribe, Selim entered national politics through the 2006 Eastern Sudan Peace Agreement, taking the post of state minister of transport and roads in 2007. For years he railed against what he called Khartoum’s “port monopoly,” arguing Red Sea revenues never reached the Beja, Rashaida and Beni Amer communities that live beside Sudan’s only deep‑water terminals. Since April 2023 he’s cast the eastern file as a litmus test: either decentralization lets coastal regions control customs, pipelines and corridor fees—or the Islamist old guard in Port Sudan keeps skimming while services collapse.

By joining TASIS, Selim is betting that the RSF‑backed charter finally hardwires revenue sharing and secular, civilian rule into law. Expect his brief to zero in on three things: prying open Port Sudan’s books, ring‑fencing a slice of customs and telecom income for local clinics and schools, and formalizing cross‑border trade so the East isn’t written off as a smuggling zone.

- Prof. Abu al‑Qasim al‑Rashid Ahmed — Governor, Northern Region • Council Member

Little is published about him beyond his academic pedigree and policy work in the Northern Region, but TASIS insiders say he’s the kind of spreadsheet-and-statute technocrat they want front‑loading decentralization. He reportedly advised local committees on budgeting and service delivery after April 2023, when Port Sudan ministries stopped wiring funds, and pushed to formalize what had been ad‑hoc community management of clinics, schools and water schemes along the Nile.

- Ahmed Faris al‑Nour — Governor, Khartoum • Council Member

A former political and humanitarian adviser in Hemedti’s circle, al‑Nour became one of the RSF’s civilian fixers for the capital once the April 2023 war shattered formal administration. While artillery duels gutted ministries and municipalities, he helped stand up emergency committees to keep water pumps running, issue temporary IDs and death certificates, and negotiate “safe windows” for evacuations and aid convoys across front lines. Inside TASIS he’s cast as the man who knows Khartoum’s labyrinth—its revenue taps, district power brokers, and how to pry services loose from Islamist-run directorates without collapsing what’s left of the city.

- Hamad Mohamed Hamed — Governor, Kordofan • Council Member

Little has been published about Hamed beyond his nomination, but TASIS insiders say he emerged from Kordofan’s wartime emergency committees. Kordofan sits on Sudan’s lifelines: gum arabic, oil pipelines, the El Obeid grain hub and the trans-Sahel trade roads. Hamed is expected to (1) standardize local levies so teachers and medics get paid instead of militias, (2) reopen courts to handle land and grazing disputes before they explode, and (3) fold community defense units into a professional security structure rather than leave them as Islamist-influenced militias,

General al-Burhan-led SAF junta in Port Sudan has denounced the civilian-led government, deepening Sudan’s two-year war-time political split.